MILAN — Vladyslav Heraskevych, the Ukrainian skeleton racer disqualified for insisting he wanted to race in a helmet adorned with the faces of athletes killed by Russia, had said he was hoping for a new “miracle on ice.”

He filed an appeal Thursday afternoon with the Court of Arbitration for Sport, asking to be reinstated — that is, to be able to race in the Olympic skeleton competition or, at the least, perform a “CAS-supervised official run pending the final decision.”

In another dimension, this would be called chutzpah.

Back to real life: was never going to happen.

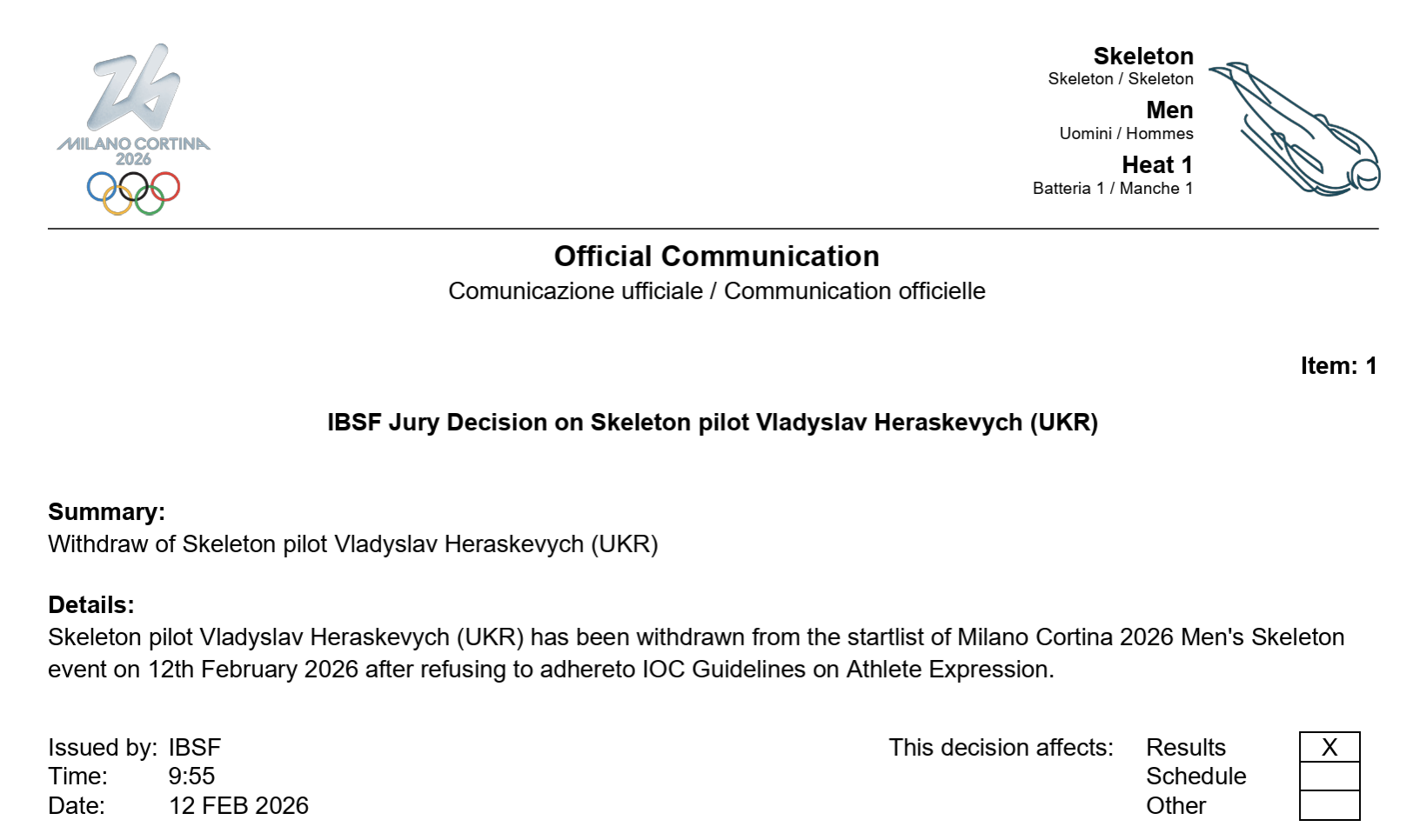

Vladyslav Heraskevych in a training run Wednesday at the 2026 Winter Games // Getty Images / Tiziana Fabi

For all the incredible — it must be said, incredible — attention the tribute helmet has drawn this first week at the Milano-Cortina Winter Games and the outpouring of support Heraskevych has drawn from across the western world, the IOC was in the right.

To be clear: in this instance, the IOC was always in the right.

In disqualifying Heraskevych, it followed its rules, which apply to everyone, and did the right thing. The sole arbitrator who decided the case said in a decision released Friday afternoon that the rules are “reasonable and proportionate.”

That is not a sentence one often writes about the IOC — it being unequivocally right.

But here, absolutely and emphatically.

This is the thing that, for the most part, got lost in the spotlight that Heraskevych (and his father, Mykhailo, also his coach) have leaned into, and hard. We will never know whether Vladyslav Heraskevych might have won a medal. We may never know whether this was their idea or he and the father did this at the urging of some — influence. We do know the son has become a national hero in Ukraine and a shining symbol in much of the West, particularly in Europe, of Ukrainian valor in the face of Russian aggression.

New from the Ukrainian post office

In a power play that underscores the power of one person to influence global opinion in the age of social media, and at lightning speed, Vladyslav Heraskevych became a way to show support for Ukraine, to shout against Russia, to decry the war, to stand up for the little guy, to complain about the IOC, to allege (without evidence, much less proof of) undue Russian influence in or on the IOC and president Kirsty Coventry — all of that and more.

The Ukrainian president, Volodomyr Zelenskyy, on Thursday awarded Heraskevych the nation’s highest honor. The post office on Friday issued a stamp in his honor. Academics and politicians from near and far lined up to proclaim their support.

And of course, here, at the end of their race Thursday night, members of the Ukrainian luge relay team raised their helmets in tribute to him.

Much of this can be summed up by this piece (translated) of an Instagram post from Heraskevych’s lawyer, Yevhen Pronin:

“… in the IOC’s view, Ukraine itself is to blame for the world’s attention being focused on it — despite the fact that this attention was caused by Russian aggression.”

This matter, though, is not a referendum on the war in Ukraine, now almost four years long — no matter how much or how many supporters of the tribute helmet might want, or desperately long, for it to be.

This is where the wave of emotion, no matter how vivid and compelling, digresses from the rules that apply in this situation — what an athlete does (or might do), says (might say) and wears (might wear) in competition at the Olympic Games.

In her ruling Friday, the sole arbitrator (name known in Olympic circles but not yet made public) said she is “fully sympathetic to Mr. Heraskevych’s commemoration and to his attempt to raise awareness for the grief and devastation suffered by the Ukrainian people, and Ukrainian athletes because of the war.”

But — the rules.

Which, in this instance, are easy to understand. It all flows from Rule 40.2 of the Olympic Charter—not Rule 50, as many have asserted online and elsewhere.

In plain English, what the rule says is there’s no room for “athlete expression” on the Olympic field of play. That is, in Olympic competition itself. None. No exceptions.

No politics, no religion, no “any other type of interference.”

That clearly — plainly, not remotely a close question — takes in a helmet paying tribute to war dead.

Some have sought to frame the matter this way: memory is not a political position.

That, though, is not it.

It’s where and how Heraskevych wanted to express the memory of war dead.

“The IOC, of course, takes into account the fact that there are 135 conflicts in which military operations are being conducted on our planet,” one of the two country’s two IOC members, Valeriy Borzov, told the Ukrainian outlet Tribuna.com in remarks posted to X.

“In this state of affairs,” Borzov, the Munich 1972 men’s 100-meter dash champion, went on, “the IOC cannot make any selective decisions because this would contradict the Olympic Charter.”

Or, in the words of the arbitrator, the rules “state that freedom of speech is a fundamental right of any athlete competing in the Olympic Games, but limit the right to express views during competitions on the field of play.”

Those rules, she said, were — to reiterate — “reasonable and proportionate,” because an athlete is free to speak to news crews gathered near the competition, in press conferences, on social networks, or, “in Mr. Heraskevych’s case, wearing his helmet during four training runs.”

Just some of the skeleton helmets here at these Winter Games, men’s and women’s, collected by Reuters

This was the point Coventry had made on Thursday.

The IOC had even suggested a black armband. Heraskevych said no. After meeting with him in the minutes just before the start of the men’s skeleton racing, trying to find compromise — he, again, said no — she said the controversy was elemental:

“No one — no one, especially me — is disagreeing with the messaging,” Coventry said later in an IOC statement. “The messaging is a powerful message. It’s a message of remembrance. It’s a message of memory.

“It’s not about the messaging. It’s literally about the rules and the regulations. In this case — the field of play — we have to be able to keep a safe environment for everyone. And, sadly, that just means no messaging is allowed.”

This was the only, and obvious, response. The right response.

If it were otherwise, in a world riven by so much conflict, the markers and statements at an Olympics would be countless. That can’t be. Imagine what might be “expressed” about the 47th president of the United States in 2028 in Los Angeles by who knows who from anywhere and everywhere. Maybe, in particular, Minneapolis.

Instead, as the arbitrator said, the “goal” of the rules is “to maintain the focus of the Olympic Games on performances and sport, a common interest of all athletes, who have worked for years to appear in the Olympic Games, and who deserve undivided attention for their sporting performances and sporting success.”

With that, it’s worth asking — why, if Heraskevych was serious about wanting to race for real in the Olympic Games in the tribute helmet, did he wait to file his claim with CAS?

Or, all along, was this about something else — the spotlight as a way (not incidentally, to pressure the IOC, which is weighing full Russian readmission) to keep a focus on the war?

Why suggest he do his own run? This situation is entirely different from the women’s 4x100 relay on the track in Rio in 2016, when the Americans got a special re-run — but only after a Brazilian runner had interfered with Allyson Felix. For emphasis: during Olympic competition, on the field of play.

Why, on Wednesday, did Heraskevych suggest on social media the IOC ought to “apologize for the pressure that has been put on me over the past few days,” and, “as a sign of solidarity,” provide Ukrainian sports facilities with electric generators?

Why, when the official DQ went out at 9:55 a.m. Thursday, was the claim not filed until 4:30 p.m.?

Britain’s Matt Weston won the event, which wrapped up Friday night, with Germans Axel Jungk and Christopher Grotheer second and third.

The tribute helmet drama started on Monday. Legal action was foreseeable. Why wasn’t there a CAS claim ready to be filed the instant the IOC announced the DQ?

“It was necessary to prepare our proposals in advance in order to coordinate with the organizers,” Borzov noted.

Another twist: the IOC has awarded Heraskevych a scholarship for each of the past three editions of the Games, real money — and here he was with this special form of thank-you?

Further, the media strategy from Heraskevych himself and his camp took a turn on Friday, and before the CAS release.

The father, Mykhailo Heraskevych, was quoted by the Ukrainian state outlet Suspilne Sport as saying, offered here as a vivid exemplar of freedom of speech, just not an athlete on the field of play:

“Miss Coventry, who is the head of the IOC, spoke about the equality of all athletes. And with this action, with the [bobsleigh and skeleton federation], she crossed out that statement because it was not about equality but about dictatorship.

“… And if the IOC leadership has any honor, they should resign immediately.”

In the same vein, he posted to X that she was an “Olympic dictator.”

The son posted to X as well, pointing out — again, freedom of speech, but why would someone purportedly keeping to the high road do this — that Coventry hails from Zimbabwe.

With deep and profound respect and the utmost of sympathy for those impacted by this senseless war — those who have lost friends and family, the wounded, the displaced— there was never going to be a legal ‘miracle on ice’ of the sort Vladyslav Heraskevych floated at that Thursday night news conference.

As the IOC said in a statement issued Friday evening, about an hour after Heraskevych landed in Germany, helmet in hand, seen later at a Ukrainian dinner on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference: “As we have said from the beginning, the IOC wanted Vladyslav Heraskevych to compete, and it was never about the message but about the place in which he wanted to display it.”