MILAN — The International Olympic Committee had no choice, really, but to disqualify the Ukrainian skeleton racer Vladyslav Heraskevych. Rules are rules.

Vladyslav Heraskevych this week with the tribute helmet // Getty Images

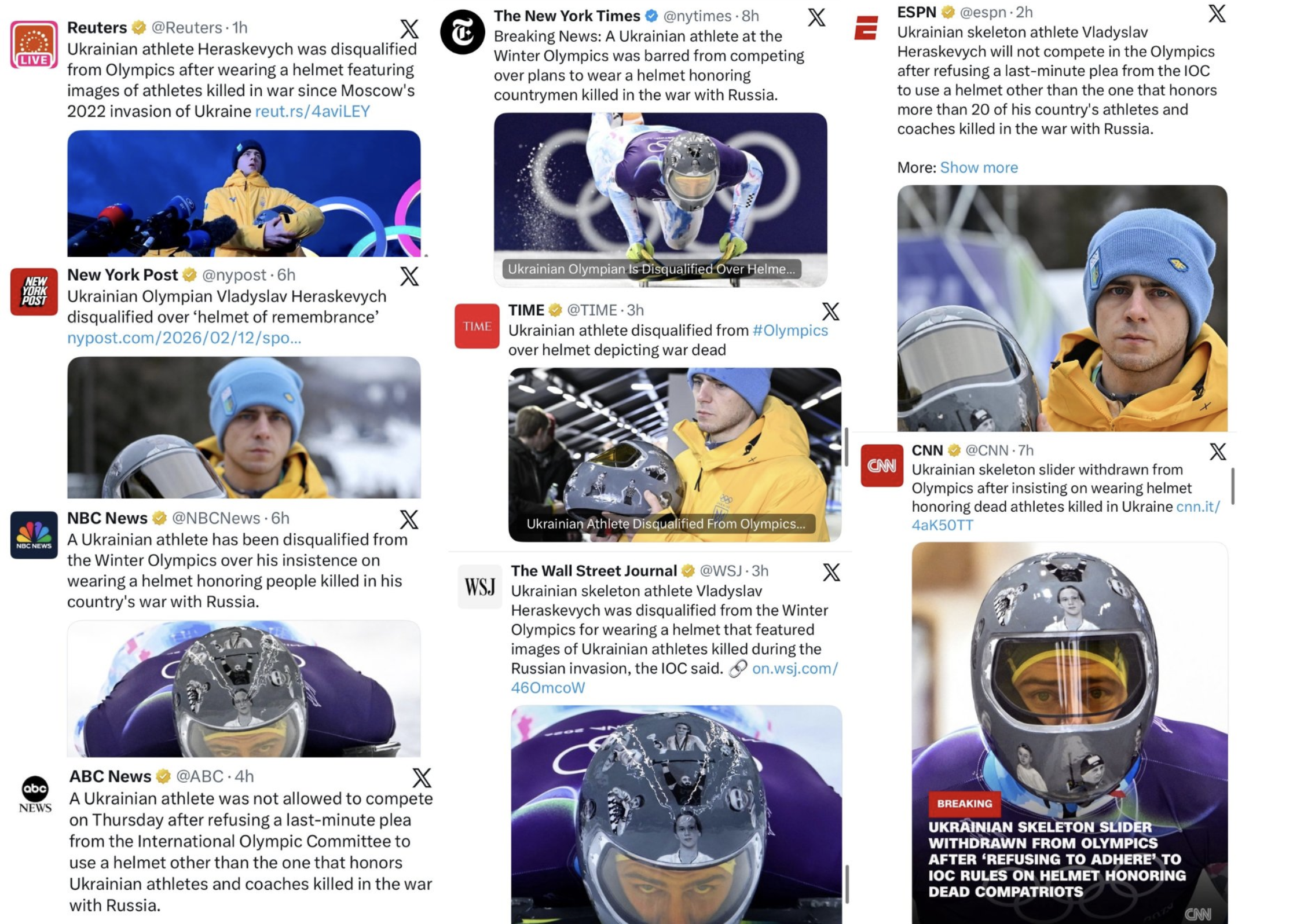

For his part, Heraskevych, by putting himself at the center of a frenzy he could know with unequivocal certainty would explode to become the centerpiece of this first week of the 2026 Milano-Cortina Games, delivered a master class in orchestrating a media strategy to maximum effect.

X / post from Ostap Yarysh

This controversy threatens to become one of the defining storylines in the history — the telling — of the 2026 Winter Games. If it’s about rules, it’s equally — if not more — about narrative and, in this context, narrative’s increasingly frequent traveling partner, raw emotion.

It’s also emblematic of one of the oldest stories in anyone and everyone’s canon: the little guy fighting the monolithic institution. From the time we learn the David versus Goliath story as small children, we are taught to root for — who?

Taking the position, as logical and rational and defensible as it might be, that, wait, there are good reasons for these rules but then looking at the faces of the Ukrainian dead on the tribute helmet that Heraskevych wore — in training and, here is the crux of the matter, sought to wear in the first runs of Thursday’s competition — was always going to play badly for the IOC.

Heraskevych put a very human face on the conflict: the faces of 20 athletes and coaches killed amid the Russian war in Ukraine. He also gave the world, which increasingly prioritizes brief hits on social media, a potent visual symbol.

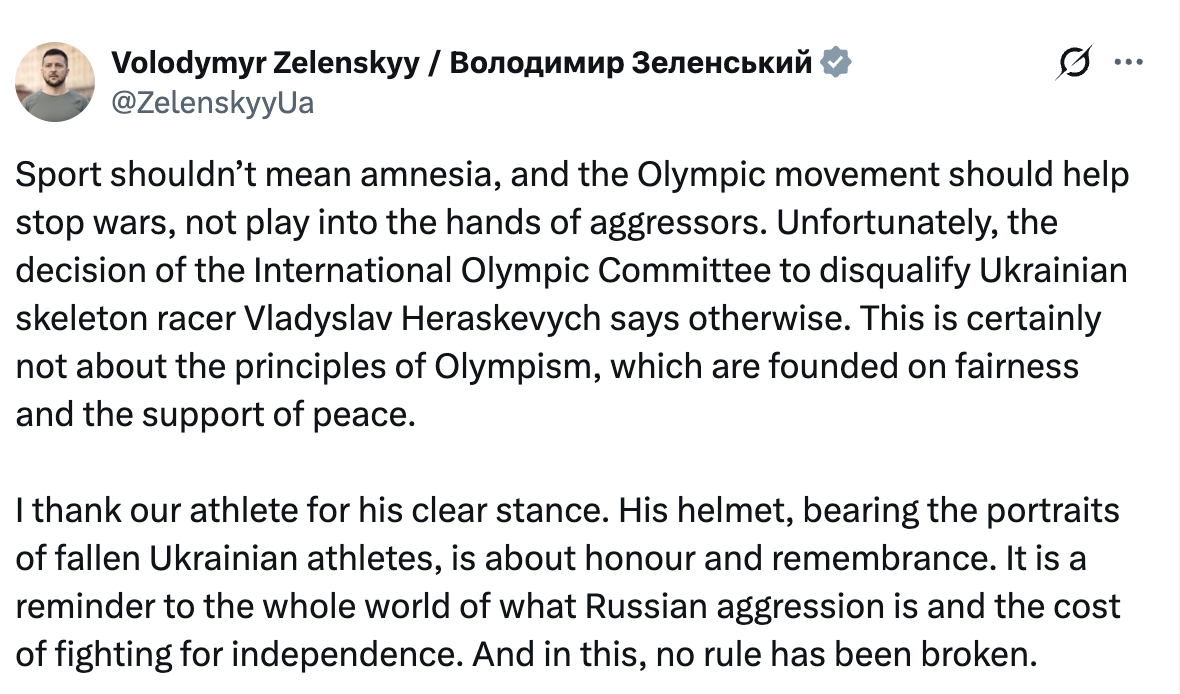

“Sport shouldn’t mean amnesia, and the Olympic movement should help stop wars, not play into the hands of aggressors,” the Ukrainian president, Volodomyr Zelenskyy, wrote on social media.

“Unfortunately, the decision of the International Olympic Committee to disqualify Ukrainian skeleton racer Vladyslav Heraskevych says otherwise.”

Everything about this necessarily has to be seen in the context of the war, the Russian military invading at the end of the 2022 Beijing Games.

It’s hardly a stretch to see what has transpired here in Milan over the past several days as a chapter in a much bigger picture.

There are 13 Russian “neutral” athletes here in Milan.

In the meantime, support for keeping Russian athletes out of the Games has seemed to be weakening in recent weeks across the Olympic and global sports landscape.

The IOC has already given the OK to Russian youth athletes, presumably with an eye on the 2026 Youth Games in Dakar, Senegal, during the first two weeks of November. If everything there goes without incident, it’s foreseeable — but hardly guaranteed — the IOC could bring the Russians back for the Summer Games in 2028 in Los Angeles.

On that score, this Thursday from the Russian foreign ministry, spokeswoman Maria Zakharova telling the TASS news service Russian officials “look forward to the full restoration of the Russian Olympic Committee’s status [with the IOC] as soon as possible and on our behalf we will support this process in every way.”

In every country but the United States, everything Olympic is an arm of the national government. Heraskevych’s father, Mykhailo Heraskevych, is president of the Ukrainian bobsled and skeleton federation and the son has said repeatedly he does not believe the Russians, even as “neutrals,” should be at the Olympics. The IOC move to allow even 13 in Milan, far from the 200-plus of a full Russian team, Vladyslav Heraskevych has said, “plays along with Russian propaganda.”

In Beijing in 2022, after his fourth and final skeleton run, he displayed a sign that declared, “No war in Ukraine.” The IOC said then he was calling for peace, and declined to find any violation of Olympic rules. That was a one-off.

It can’t be a surprise that Heraskevych served as Ukraine flag bearer at last Friday’s opening ceremony.

On Monday, as practice got underway, he appeared at the track with the tribute helmet.

In a 2023 interview with a German outlet, Heraskevych said, “The war has changed me, of course. I’m a different person now.

“I’ve become cynical. If you’re too emotional, it’s unbearable … I used to be much more emotional. Now I’m just in shock. It’s like another world, a world I don’t like.”

Now, the IOC rule at issue:

IOC president Kirsty Coventry Thursday morning after meeting with Vladyslav Heraskevych // Getty Images

It’s Rule 40 — not 50, as many have wrongly asserted — of the Olympic Charter. The IOC updated Rule 40 in 2019 after consultation with 3,500 athletes — this while Kirsty Coventry, now the IOC president, was head of the IOC athletes’ commission.

For this discussion, the key part of Rule 40 is 40.2: if you’re inside the Games, you “shall enjoy freedom of expression in keeping with the Olympic values and the fundamental principles of Olympism, and in accordance with the guidelines determined by the IOC executive board.”

What does that mean?

The IOC’s Athlete 365 portal holds the document that explains:

“It is a fundamental principle that sport at the Olympic Games is neutral and must be separate from political, religious or any other type of interference. Specifically, the focus on the field of play during competitions and official ceremonies must be on celebrating athletes’ performances …”

Earlier this week, the American curler Rich Ruohonen, 54, a lawyer, the oldest American ever at a Winter Games, said in an interview about Minnesota, where he lives: “… what’s going on there is wrong.”

He added, “We have inalienable rights in our Constitution. Freedom of press, freedom of speech, the right to not have unreasonable searches and seizures and not be pulled over for, you know, without probable cause. And those rights aren’t being followed in Minnesota.”

Under Rule 40, zero problem with these remarks. Why? None of these comments came on the field of play.

Ruohonen got into the action on Thursday in a match against Switzerland. Now this hypothetical: imagine if, during that match, Ruohonen had pasted pictures of Renee Good or Alex Pretti or both on his broom. (For emphasis: he did not do that. This is a hypothetical.) What daylight is there between that and a tribute helmet to those killed since 2022 in Ukraine?

The rules, per the IOC, are the rules.

There are distinctions easily drawn between the Heraskevych tribute helmet and other episodes here in Milan.

American skater Maxim Naumov in kiss-and-cry // Getty Images / Matthew Stockman

The U.S. skater Maxim Naumov brought a photo of him with his parents — they were among the 67 killed in the January 2025 plane crash near Washington — to kiss-and-cry.

In the opening ceremony, an Israeli, Jared Firestone, wore a kippah — the Jewish head covering — with the names of the 11 Israeli athletes and coaches murdered by Palestinian terrorists at the 1972 Games. The kippah was under a hat.

Cortina flagbearer Jared Firestone // Getty Images / Mattia Ozbot

Are these rules violations? The ceremony is without question “field of play.” Both instances, at least for now, however, are one-offs and, in keeping with the way the IOC typically handles a one-off, neither has faced, or is likely to face, sanction.

The IOC is hardly — stress, hardly — trying to single out the Ukrainians for discriminatory treatment, and there’s an argument the case is just the opposite. It’s a legitimate question whether the — or at least some number of the — Ukrainians are, deliberately or otherwise, targeting the IOC.

At the world fencing championships in 2023, Ukrainian fencer Olga Kharlan was disqualified because she would not shake the hand of a Russian opponent. Then-IOC president Thomas Bach stepped in to guarantee her a slot at the Paris 2024 Games, where Kharlan won individual bronze and team gold.

Here in Milan, two more episodes involving helmets and the Ukrainian team:

Freestyle skier Katia Kortsar’s helmet had said, “Be brave like Ukrainians.” She said the IOC sent her an email a week ago saying, not OK. So she changed it. Short track speed skater Oleg Handy’s helmet bore the phrase of the poet Lina Kostenko: “Where there is heroism, there is no final defeat.” He said he was told to tape it over, and would do so.

Compare:

Heraskevych wore the tribute helmet starting with practice runs Monday. Practice ran through Wednesday. He said he fully intended to wear it while racing for medals. At a news conference Tuesday, he said he would wear the helmet while racing. With that, the IOC said, he “publicly conveyed the message that he would openly defy” the rules.

On Wednesday afternoon, it said, he confirmed in writing he intended to wear the helmet.

On Tuesday, the IOC had offered a compromise — a black armband. It would go on to say he could bring the helmet with him in meeting reporters.

Heraskevych’s response on social media: the IOC ought to “apologize for the pressure that has been put on me over the past few days,” and, “as a sign of solidarity with Ukrainian sport, provide electric generators for Ukrainian sports facilities that are suffering from daily shellings.”

He also insisted on wearing the helmet while racing.

This, for the IOC, is the bright line.

The athletes’ commission, now headed by Emma Terho of Finland, issued a statement that said, in part, “The key point to note [is] that it is not about the message that Vladyslav is trying to convey, it is about the place (i.e. field of play during competition).”

Coventry took the pointed and unusual step of meeting early Thursday morning with Heraskevych, before the first two runs of the men’s Olympic skeleton got underway.

From an IOC perspective:

The IOC has for the last three editions of the Winter Games supported Heraskevych with real money — what’s called a Solidarity scholarship, one of precisely 449 in the entire world in the lead-up to the 2026 Olympics. Too, since 2022 the IOC has undertaken a special, wider $7.5 million program to aid Ukrainian athletes and coaches.

Heraskevych would not budge.

“No one — no one, especially me — is disagreeing with the messaging,” Coventry said later in a statement issued by the IOC. “The messaging is a powerful message. It’s a message of remembrance. It’s a message of memory.

Mykhailo Heraskevych learning of the IOC DQ — the racer’s father and coach and, as well, president of the Ukrainian bobsleigh and skeleton federation // Getty Images

“It’s not about the messaging. It’s literally about the rules and the regulations. In this case — the field of play — we have to be able to keep a safe environment for everyone. And, sadly, that just means no messaging is allowed.”

The IOC, an institution keenly devoted to rules and process, can say it stuck to its rules. It can say it did the right thing, the only thing it could do.

“Sport without rules cannot function,” IOC spokesman Mark Adams said late Thursday morning at a news conference, adding a moment later, “If we have no rules, we have no sport.”

The IOC action after the early Thursday meeting with Coventry was not just the DQ but a move to strip Heraskevych of his credential. Then, Coventry said, “on an exceptional basis, after the very respectful conversation with the athlete,” it was agreed he could stay on Olympic grounds, despite not being able to compete.

Late Thursday, Heraskevych posted on X about IOC “cynicism” and “the wrongful disqualification and robbing me of my Olympic dream,” then said, in reference to the IOC president’s decision to let him stay in the village, “Thank you for your ‘kind’ heart, IOC.”

A few hours before that, it might be noted, Zelenskyy awarded Heraskevych Ukraine’s highest honor, the Order of Freedom, saying the nation “is proud of Vladyslav and his act,” adding, “Having courage is more than medals.”

There’s a quote attributed to the American author Carl Sandburg that would here seem apt:

“If the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts. If the law and the facts are against you, pound the table and yell like hell!”