Three years ago, in the space of a week, 40 track and field athletes in Turkey were suspended for doping offenses. Each got a two-year ban. Of those 40, 31 came in a one-day chunk. Of those 31, 20 were 23 or younger.

Did track and field’s international governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federations, move to ban Turkey? No. Was what happened in 2013 within the current four-year Olympic cycle? Obviously. And yet — the IAAF is seeking now to effect a ban against Russia, and 68 track and field athletes, for the Rio Games? Logically: explain the difference, please.

If only.

At a hearing Tuesday, the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport — meeting behind closed doors — took up the matter of the Russian ban. An appeal, brought by the Russian Olympic Committee, challenges the IAAF action last November, upheld last month, that seeks to suspend the Russian track and field federation and those 68 athletes, including pole vault diva Yelena Isinbayeva, from the Games amid allegations of a state-sponsored doping conspiracy.

CAS intends to deliver a ruling Thursday. That decision is widely expected to help guide International Olympic Committee policy heading toward the Aug. 5 start of the Games.

Leaving the hearing, Isinbayeva told Russia 24, a state-owned news channel, that she was “optimistic.”

She should be.

-- Yelena Isinbayeva on her Instagram account from Tuesday's CAS hearing in Switzerland --

The case pits the notion of collective responsibility against what is elemental in any system of justice, individual adjudication.

Because the CAS hearing was conducted in secrecy, nobody knows what was discussed, or what the three-member CAS panel might have asked.

Like the matter of the Turkish track and field bans three years ago, which assuredly provides an intriguing precedent, the only limit to what might have been asked is the imagination.

Here, then, are a variety of queries that might have been, should have been, maybe even were asked:

— The presumption of individual innocence is a bedrock principle in the law. Why should that presumption be stood on its head in this matter?

— In theory, this CAS case is limited to track and field. However, since any decision is likely to weigh significantly on any IOC action, please answer this fundamental inquiry: why, if a Russian track and field athlete might be banned, should a Russian synchronized swimmer or gymnast — with no record of doping, per the report advanced Monday by the respected Canadian law professor Richard McLaren — be similarly affected?

Doesn’t that underscore all the more the imperative for individualized justice?

— The IAAF task force that reported in June to the federation’s policy-making executive council asserted, at point 5.2: “A strong and effective anti-doping infrastructure capable of detecting and deterring doping has still not yet been created. Efforts to test athletes in Russia have continued to encounter serious obstacles and difficulties; RusAF appears incapable of enforcing all doping bans; and RUSADA is reportedly at least 18-24 months away from returning to full operational compliance with the World Anti-Doping Code.” RusAF is the Russian track and field federation, RUSADA the nation’s anti-doping agency.

These absolutely are serious allegations deserving of careful consideration. At the same time, these same allegations could be made of any of dozens of nations in our world. To name just a few of note in the track and field context: Kenya, Ethiopia, Jamaica. Why a ban aimed only at Russia?

In noting Russian sports minister Vitaly Mutko’s assertion that “clean Russian athletes should not be punished for the actions of others,” the IAAF task force responded, at point 6.1: “There can only be confidence that sport is reasonably clean in countries where there is an engrained and longstanding culture of zero tolerance for doping, and where the public and sports authorities have combined to build a strong anti-doping infrastructure that is effective in deterring and detecting cheats.”

Same question: why Russia only when reason and logic dictate a lack of confidence elsewhere in the world as well?

Jamaica, for instance, contributed only $4,638 toward WADA’s $26 million 2016 budget. Kenya and Ethiopia, $3,085 apiece. How do such contributions in any way suggest legitimacy in the campaign to ensure doping-free sport?

— From the same June IAAF task force report: "At a time when many athletes and members of the public are losing confidence in the effectiveness of the anti-doping movement, the IAAF must send a clear and unequivocal message that it is prepared to do absolutely everything necessary to protect the integrity of its sport ..."

Doesn't this sort of rhetoric merely confirm the theory, advanced by many, that the IAAF bid to ban the Russians is nothing but a play rooted in politics and, as well, public relations?

That the IAAF took the easy way out with the understanding that, per the checks and balances built into the international sport system, this court could then address the Russian grievance -- the IAAF knowing it could then proclaim it had been tough but got overruled by sport's judicial branch?

-- In a bid to remediate the ban, the IAAF established this policy:

"If there are any individual athletes who can clearly and convincingly show that they are not tainted by the Russian system because they have been outside the country, and subject to other, effective anti-doping systems, including effective drug-testing, then they should be able to apply for permission to compete in International Competitions, not for Russia but as a neutral athlete."

Remediation is a basic principle of law. When such a policy permits one or perhaps two of 68 to qualify, how is this sort of remediation in any way reasonable or fair?

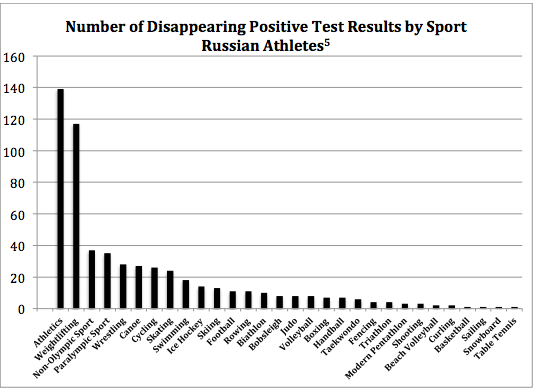

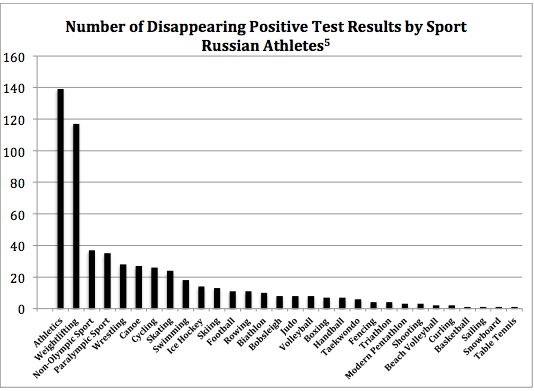

— Mr. McLaren's report, commissioned by the World Anti-Doping Agency, alleges state ties in the wide-scale doping of Russian athletes, and across various sports.

The report suggests that such evidence rises to the level of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.” Has any of that evidence been tested in a formal tribunal, in particular by cross-examination? If not, isn’t any claim of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” empty?

— Mr. McLaren’s report says that he would have offered more evidence but he ran out of time. Is it a coincidence, or something more, that Monday, July 18, was an IOC deadline for “entry by name” to the 2016 Games? Is that why Mr. McLaren’s report came out that morning?

More: if Mr. McLaren wanted or needed more time, why didn’t he just take it and provide a more thorough inquiry?

— Mr. McLaren’s report offers literally no proof that Mr. Mutko authorized any of the alleged misconduct it details. Without such evidence, how can a broad-based sanction stand?

— Switching to technical matters, first the Olympic Charter.

Rule 27.3: the national Olympic committees hold “the exclusive authority for the representation of their respective countries at the Olympic Games.” Again, “exclusive.” That means, in this instance, the Russian Olympic Comnittee.

On what legal grounds does the IAAF, an international federation, assert it has the right to interfere with such exclusivity?

Back up to Rule 26.1.5. The IFs, the Charter says, “assume the responsibility for the control and direction of their sports at the Olympic Games.” Nowhere does that rule provide an IF any say over entries.

But Bylaw 2.1 to Rules 27 and 28 does: the NOCs “decide upon the entry of athletes proposed by their respective national federations.”

More on the same point:

Rule 40 says a “competitor” must “respect and comply with the Olympic Charter and World Anti-Doping Code.” The Russians assert they have been submitting to regular testing over the past several months.

Bylaw 1 to that rule says each IF “establishes its sport’s rules for participation in the Olympic Games, including qualification criteria, in accordance with the Olympic Charter.” Again, not entry.

When the Charter seeks to use the word “entry,” it does so. Rule 44 declares, “Only NOCs recognized by the IOC may submit entries for competitors in the Olympic Games.” Not an IF. And no note here about IF review of any entries.

Bylaw 4 to Rule 44:

“As a condition precedent to participation in the Olympic Games, every competitor shall comply with all the provisions of the Olympic Charter and the rules of the IF governing his sport. The NOC which enters the competitor is responsible for ensuring that such competitor is fully aware of and complies with the Olympic Charter and the World Anti-Doping Code.”

Rule 46 details the 'role of the IFs in relation to the Olympic Games." Bylaw 1.7:

“To enforce, under the authority of the IOC and the NOCs, the IOC’s rules in regard to the participation of competitors in the Olympic Games.”

To emphasize: doesn’t that plainly relegate an IF such as the IAAF to the secondary role of “enforcing” participation “under the authority” of the IOC and, in this instance, the Russian Olympic Committee?

— The World Anti-Doping Code, in Article 10, explicitly envisions sanction only when an individual athlete is tied to specific misconduct. How to jibe a broad ban with the Code?

— The Code, Article 11: “In sports which are not Team Sports but where awards are given to teams, Disqualification of other disciplinary action against the team when one or more team members have committed an anti-doping rule violation shall be as provided in the applicable rules of the International Federation.” How can the IAAF apply a broad ban to an entire “delegation” when the rules specifically call for sanction against a “team” such as a 4x100 relay?

— Again from Article 11: consequences against teams are premised on an “Event” or “Event Period’ such as the period of an Olympic Games. There is no “Event” here. How can a broad sanction against the entire Russian delegation, not a team, stand?

— The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency’s charge was, essentially, to be a contractor. When, exactly, did USADA — which has been lobbying furiously in the Russian matter — become a self-proclaimed Olympic movement “stakeholder”? And is that appropriate?

— Like USADA, the IAAF has said it broadly seeks to promote — to take from an IAAF news release — “clean athletes and sport justice.” Is it really here to protect “clean athletes”? Or to protect just the ones it wants to protect?

— Outside each and every U.S. Post Office flies an American flag. The U.S. Postal Service served for years as the primary sponsor of Lance Armstrong’s team during the Tour de France. USADA’s “Reasoned Decision” calls the Armstrong matter “a massive doping scheme, more extensive than any previously revealed in sports history.” What is the distinction between, on the one hand, sponsorship by an independent agency of the U.S. government and, on the other, what is alleged to have happened in Russia?

Cycling’s worldwide governing body, the UCI, did not move to ban the entire American cycling team. Yet the IAAF is seeking to ban the Russians.

Really?