OMAHA — One more time, now, everyone: Michael Phelps and Ryan Lochte in the 200-meter individual medley.

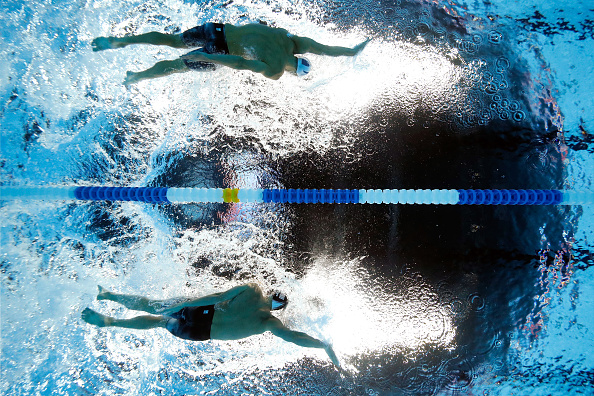

In the latest edition of what has been one of the great rivalries in sport, any sport, anytime, anywhere, Phelps and Lochte on Friday night went 1-2 in the 200 IM at the 2016 U.S. Swim Trials.

That sends both familiar faces to Rio to get it on one more time in what is indisputably one of the hardest events in swimming: 50 meters each of butterfly, backstroke, breaststroke and a killer freestyle sprint to that final wall.

Phelps went 1:55.91 for the win, Lochte touching in 1:56.22.

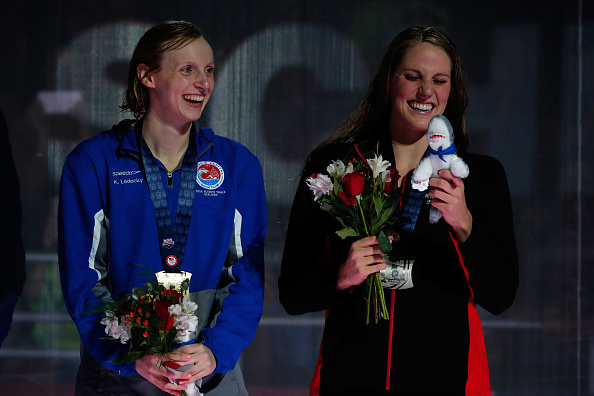

During the victory ceremony, Phelps wrapped his right arm around Lochte’s shoulder. The crowd, 11,497 people at Century Link Arena, roared. Later, the two of them would hold hands high, like boxers of yore who had just slugged it out but retained for each other the fullest measure of respect.

Walking off the stand, they got hugs from Kaitlin Sandeno, the Sydney 2000 and Athens 2004 swim medalist who is here as a poolside announcer. She turned to the cameras and said, “That was the showdown this crowd came to see. We all just saw what we all assume was the last race between you two on U.S. soil. Probably a lot of disappointed, sentimental fans out there,” and the crowd erupted again.

When he got the microphone a moment later, Phelps said, “We have been racing since 2003, 2004, and I can honestly say I don’t know if there’s another person in this world that I race who brings the best out of me like he does. We leave it all out in the pool.”

Lochte echoed the sentiment: “There’s no other person I would be happy to race against.”

As evidence of how much better Phelps and Lochte are than anyone else in the 200 IM, this:

David Nolan, third, finished in 1:59.09. That’s 3.18 seconds behind Phelps. That’s a huge chunk of time in a 200-meter race.

Watching Lochte and Phelps in the 200 IM is at once past, present and future.

Past:

Athens 2004: Phelps 1, Lochte 2.

Beijing 2008: Phelps 1, Lochte 3.

London 2012: Phelps 1, Lochte 2.

World championships:

Kazan 2015 and Barcelona 2013, events in which Phelps didn’t swim: Lochte 1.

Shanghai 2011: Lochte 1, Phelps 2 — the race in which Lochte lowered the world record to 1:54 flat and Phelps, in the midst of his kinda-sorta trying phase, acknowledged that if he wanted to win he, you know, had to train like it.

As Lochte said late Friday, "You know, the one that -- the 200 IM racing against him that stands out the most would have to be when I broke the world record back in 2011, just something that unexpected, that got people excited for me. Being able to do that and get a world record definitely was a dream come true.

"But, you know, racing against him is fun."

Present:

Leading into these Trials, Phelps finally has taken up his own 2011 advice. He has trained hard, and it shows. His strokes look big and sweeping and at the same time easy. He is once again riding high in the water — the way he did nine years ago at the Melbourne 2007 worlds and, so memorably, at the 2008 Olympics.

Mentally, and this is truly the key, Phelps is in a totally different space than he was going into the Games four years ago. He turned 31 on Thursday. He is a new father. He talks appreciatively about living in the moment and enjoying the experience of being in and around the pool, and the swimming community.

Lochte observed late Friday, “You can definitely see a difference in Michael this past year, past year-and-a-half. Just his overall attitude: he’s in a much-happier place. I’m definitely really happy for him.”

Phelps extended the news conference that ended Friday night's proceedings to take one extra question, from the 10-year-old daughter of swim star-turned-broadcaster Summer Sanders: Will Boomer, his two-month-old, swim? "I don't know if he's going to be a swimmer," the world's most famous swimmer, ever, said. "If he is, I'll give him some pointers," adding, "I'll leave it to him."

For Lochte, who is also 31, turning 32 two days before the start of the Rio Games, Friday’s race was something of do-or-die. Phelps had earlier qualified in an individual event for the 2016 U.S. team, an unprecedented fifth Games for a male American swimmer, in the 200 butterfly. Lochte had run third in the 400 IM — out — and then took fourth in the 200 free, meaning he was on the U.S. team but only for relay consideration.

The two men had set the top times in qualifying, Lochte in 1:56.71, Phelps 1:57.61.

Reviewing the top-five marks in history in the event: Lochte has the top two, Phelps the next three.

“I think it's one of the greatest rivalries in sports, me and him, just from what we have both done, and it's definitely fun,” Lochte had said after the semifinals. “It's fun racing against him, and it's competitive out there.”

Lochte has been swimming here in Omaha with a badly strained groin; he pulled it in his very first race, the 400 IM. That’s in large measure why he took third in the 400 IM final, a race in which he won the gold medal in London four years ago.

“Definitely — I took some painkillers to help me, help the pain earlier today, Advil and whatever, just helped my mind with the pain,” he had said after the 200 IM semis. “First part of the breaststroke felt good and halfway through it started hurting more and more, until the last couple of strokes, and I was able to get in.”

For his part, Phelps said after the Thursday semis, “Him and I have gone back and forth a number of times in this race and during the big meets. We have great races and, you know, we're right there with each other tomorrow in the middle of the pool, couple lanes apart, and it's going to be good.

“We're going to be out and probably step on the gas a little bit more than we have in the past and you'll have an exciting race.”

As they walked to the blocks, Lochte gave Phelps a "flat tire" -- slang for stepping on the back of someone else's shoe so it falls off. They laughed.

"I was just really close to him," Lochte said, "and I accidentally give him a flat tire, and he was like, 'Are you trying to mess me up before the race?' And I was like, 'No, no, I was just joking.' "

"We both are just loving life and loving what we are doing," Phelps would say later with a smile. "I think it shows that we are both enjoying ourselves."

Until race time. Then -- fun time was, appropriately, over.

The race played out just as Phelps predicted -- actually, almost exactly the same way this race went down at the 2012 Trials.

Phelps, just as in 2012, would lead wire-to-wire.

Lochte was third at the first turn, after the butterfly; then moved to second for good during the backstroke, obviously one of his specialties.

During the final 50 meters, the was rocking big-time. Phelps swam that freestyle leg in 28.27; Lochte in 28.39.

Final difference: 31-hundredths of a second.

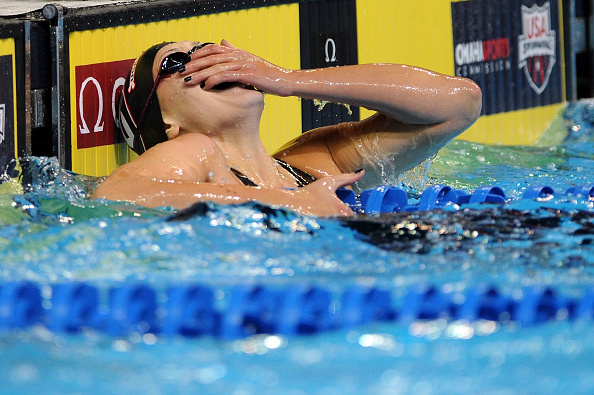

"First thing I thought," looking up at the scoreboard, "was it was a good race, and when I knew -- when I looked up and saw that I was second, I was, like, you know, at least it's not in the Olympics," Lochte said. "I still have another month to really tweak some things in the race and just hopefully become better."

Because of his reality-TV antics and the frat-boy public persona he can affect, Lochte can get a bad rap — way, way, way too many people thinking he can hardly make change for a dollar, much less count to 200 meters.

What a misconnect.

Lochte is one shrewd dude. He is not only smart but sensitive, funny and profoundly loyal. He is also — believe it — as tough as they come.

Lochte limped Friday away from the pool, testament to how deep he had to pull to make the team.

"I mean," he said, "I could have a broken leg, and I would still go on the blocks and race."

As for the future:

The times that Phelps and Lochte put down Friday made for the second- and third-fastest in the world in the 200 IM in 2016.

Even so, if obviously, neither is by no means guaranteed 1-2 or 1-3, or anything, in Rio.

"I do have to swim faster if i want to win the gold medal," Phelps said. "I do know that."

The world’s No. 1 time this year in the 200 IM belongs to Japan’s Kosuke Hagino. In April, he went 1:55.07.

Another Japanese swimmer, Hiromasa Fujimori, went 1:57.57, also in April. Before Friday night, that had been the world’s No. 3 2016 200 IM swim.

Then there is this, an often-overlooked nugget that may have as much to do with the Rio race as anything:

For the past Olympic cycles, Lochte has chased Olympic medals in both the 200 backstroke and the 200 IM.

He is the Beijing 2008 gold medalist, the London 2012 bronze medalist in the 200 back.

The Olympic schedule puts the finals of the 200 back and 200 IM on the very same night, just minutes apart.

It is a credit to Lochte’s fortitude and want-to that he lined it up in both races.

That said, it’s a fact that the backstroke is all about the legs. Way more than the arms. And swimming the 200 back absolutely takes something out of everyone’s legs. No matter how tough.

Here in Omaha, Lochte opted out of the 200 back. After the third in the 400 IM, he was in practical terms looking only at the 200 IM. (He swam in the prelims of the 100 fly, placing ninth, good enough for Friday’s semis, but predictably scratched.)

In theory, come Rio — assuming Lochte’s groin is better in a month — his legs should be way more fresh for that 200 IM.

In Rio, Lochte observed, “I don’t have to worry about doubling up in any events. I’m excited.”

Phelps, meantime, was out of the pool after the 200 IM at 7:47 p.m. He was back in 27 minutes later, at 8:14, for the first semifinal of one of his best events, the 100 fly. He took third in 51.83, good enough to move on to Saturday’s final.

Phelps hasn't pulled a double like that in -- a long time. "Tonight was brutal," he said. "That hurt. The 100 fly hurt."

He added a moment later, "I’m going to get a massage. I’m going to sit in a 50-degree ice tank. I’m going to go home and pass out

“We’ve had a long history,” Lochte had said Friday on the pool deck. “A long journey. But the journey’s not over."

“… We will have a very good, very fun, exciting race for you guys,” Phelps said, referring to Rio.

He added: “Stay tuned.”