BEIJING — For this world championships year, 2015, the U.S. 4x100 men’s and women’s relay teams had one objective, and one objective only: get the stick around. Really. The trick was not to fall prey to the dropsies, oopsies and bumps in the night that have for far too long at major meets have plagued American entries.

With several young runners on the track and and the idea of using the 2015 worlds as an end unto itself but also a means of preparing for the 2016 Rio Olympics, the verdict Saturday: oops, again!

At first, it appeared the Americans had pulled second-place finishes in the 4x1, both times behind the Jamaicans.

The U.S. women turned in a season-best effort.

But then the U.S. men were disqualified for a gruesome-looking third pass, Tyson Gay to Mike Rodgers -- out of the zone.

To win at this level, everything has to go right. It's very complex. But at the same time, very simple. Veronica Campbell-Brown, the Jamaican veteran, offered the summation of what they do right and the Americans consistently find a struggle: "We executed well, we finished healthy and we won."

This next-to-last night of the 2015 worlds offered great performances not just on the track but in the field events as well.

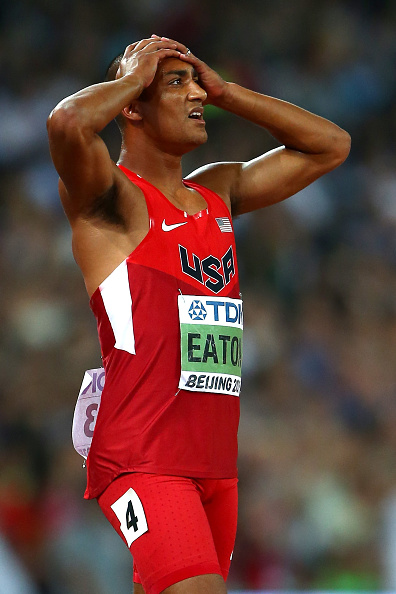

In the decathlon, the American Ashton Eaton went into the last event, the 1500, needing a 4:18.25 or better to break his own world record, the 9039 points he put up at the 2012 U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon.

Beyond pride and records, don’t think he didn’t want the record, even if this is a non-Olympic year; it would mean, given bonuses and roll-overs, six-figures plus.

His wife, Brianne Theisen-Eaton, the Canadian silver medalist heptathlete here and at the Moscow 2013 worlds as well, tweeted about an hour before he would run:

To go 4:18, Eaton would have needed to keep to this pace: 1:08 at 400 meters; 2:17, 800; 3:26. 1200; 4:18, finish.

In Eugene in 2012, Eaton had run a personal-best 4:14.48.

Michael Schrader of Germany hit 400 in 1:09.34, Eaton back in the pack; Larbi Bourrada of Algeria 800 in 2:21.56, Eaton one step behind; Bourrada at 1200, stretching it out, 3:31.61; Eaton ran hard down the homestretch, chasing Bourrada, who crossed in 4:16.61.

Eaton, 4:17.52.

Clear by 73-hundredths of a second.

Eaton fell to the track, then got up and staggered toward the sidelines, hands on knees, before climbing over the rail to give his wife a hug. The picture of exhaustion, he literally needed help getting back over the railing.

The new world record: 9045 points.

His performance included a decathlon event world record 45-flat Friday in the 400; Bill Toomey had run 45.63 in 1968.

He said later about Brianne, "She’s — it can’t be summed up in words but I now I would not have done what I did today without her."

He also said about the emotion that welled up after his victory, "The older I get," and he's 27, "the more I realize we're making choices to have the experience we're having. Those choices involve giving up a lot of stuff.

"You just feel like you miss a lot, friends, family ... it is just an accumulation of those feelings, and when you do something you just realize, I am doing it for a reason, and when that reason manifests itself it's pretty emotional."

Canada’s Damian Warner took decathlon silver, 8695, a national record; Rico Freimuth of Germany third, in a personal-best 8561.

"When Ashton broke the world record, the feeling on my skin was unbelievable," Freimuth said, adding, "I told him he is the greatest athlete."

Breaking the world record by less than that one second carried with it a slight irony. At the 2014 world indoors in Sopot, Poland, Eaton missed breaking his own heptathlon world record in the final event, the 800, by — one second.

"That was a gutsy 1500, huh?!" Harry Marra, who coaches Eaton husband and wife, said later -- and the results both put up underscore what a world-class coach that Marra, after many years in the sport, continues to be.

Eaton said that before the 1500, "I was doubting myself in the restroom, thinking, I don't know if I can run that." Then he thought, "I have a lot of people who believe in me … and they were all saying, you can do it. I was like, yeah, think I can."

Earlier Saturday evening, Britain’s Mo Farah completed the distance triple double, winning the men’s 5k with a ferocious kick to cross in 13:50.38. He won the 10k earlier in the meet.

With the victory, Farah became the 5 and 10k champion at the 2012 Olympics, 2013 worlds and, now, here.

The winning time, 13:50.38, was the slowest in the history of the world championships, dating to 1983. The previous slowest: Bernard Lagat, 13:45.87, at Osaka, Japan, in 2007.

Farah ran the last 400 meters in 52.7 seconds, the last 200 in 26.5. "The important thing," he said, "is to win the race, and I did that."

Americans in the 5k: 5-6-7.

For the first time ever at a world championships, the women’s high jump saw six athletes go over 1.99 meters, or 6 feet, 6-1/4 inches.

Russia’s Maria Kuchina won at 2.01, 6-7, the 0ft-injured Croatian star, Blanka Vlašić, taking second, also at 2.01 (she had one earlier miss, at 1.92, 6-3 1/2), tearfully blowing kisses to the crowd after her last jump.

Vlašić now has two worlds golds and two silvers; she took silver at the Beijing 2008 Games. This was Kuchina’s first worlds; she registered an impressive six first-time clearances Saturday before being stymied at 2.01. Another Russian, Anna Chicherova, the London 2012 gold and Beijing 2008 bronze medalist, took third, also 2.01 but with two earlier misses.

"Today I showed that I am still there, that it is not over," Vlašić said.

Since 2003, meanwhile, there had been 13 major sprint relay competitions before Saturday night — Olympics, world championships and, the last two years, World Relays.

At those 13, U.S. men had botched it up — drops, collisions, falls, hand-offs outside the zone — seven times.

Add in a retroactive doping-related DQ from the Edmonton 2001 worlds, and the scoreboard said eight of 14. Dismal.

U.S. women: five no-go’s going back to 2003, four in the sprints, one collision in the 4x1500 in the Bahamas in 2014.

There’s a women’s retroactive Edmonton 2001 doping-related DQ, too. So that would make it six.

It’s not as if the athletes, coaches and, for that matter, administrators at USA Track & Field are not aware of the challenge.

Indeed, after the 2008 Summer Games here at the Bird’s Nest, USATF commissioned a thorough report on the matter, dubbed Project 30; in those Olympics, both men’s and women’s 4x1 relays dropped the baton on the exchange to the anchor, Torri Edwards to Lauryn Williams, and Darvis Patton to Tyson Gay.

The Project 30 report identified a host of institutional and structural challenges, and potential reforms, including more training camps.

What followed that next summer, at the Berlin 2009 world championships: the women’s 4x1 team DNF’d in the heats, the men’s 4x1 effort got DQ’d in the rounds.

It hasn’t, of course, been all bad.

At the 2012 London Games, the U.S. women 4x1 ran to gold and a world-record, 40.82.

The U.S. relay program has this year been under the direction of Dennis Mitchell, the Florida-based former sprint champion who is now coach of, among others, Justin Gatlin.

He is so in charge that when, at a pre-meet news conference, U.S. team coaches Delethea Quarles (women) and Edrick Floréal (men) were asked about who might run in the relays, each said, it’s up to Mitchell.

It wouldn’t be a championships without some measure of, ah, observation from many quarters — fans, agents, press reports — about which Americans are doing what, or not, in which relay.

For instance, Tori Bowie, the bronze medalist here in the women’s 100, in 10.86, didn't run. Why?

Bowie is sponsored by adidas; the U.S. team by Nike. At the Diamond League meet earlier this summer in Monaco, to run in the relays you had to wear team gear. Some adidas athletes chose not to -- meaning they chose not to run. For emphasis, the U.S. team did not say, don’t run because you are sponsored by adidas; indeed, the U.S. team said please do run, in national-team gear.

The predictable upshot, this quote from Bowie’s agent, Kimberly Felton: “Of course, she would love to run the relay and support her country.”

Well, sure. But a little context, please, because, as always, things just aren’t black and white.

In Monaco, Bowie attended one practice, according to USATF. Her representatives then informed USATF she would not be competing there and would not be part of the relay pool going forward, including the camp in Japan. To not stay part of the program — that was all from Bowie’s side.

This statement, in full, earlier this week from USATF:

“Our men’s and women’s sprinters were invited to Team USA relay camp in Monaco in mid-July and to Team USA’s overall World Championships training camp in Narita, Japan, this month. In order to ensure quality relay performances and success in Beijing, athletes were required to attend both camps and to actively participate in all practices. With a relatively high number of new, talented sprinters emerging this year, these practices were especially important for practicing exchanges and determining relay position. Tori Bowie’s representatives informed us that she would not compete in Monaco and later said she would not be moving forward with the relay process or attending camp in Narita. We moved forward, practicing with and planning for the athletes in attendance. We look forward to our relays taking the track on Saturday.”

If this all seems like something new, consider:

At those Osaka 2007 worlds, the American sprinter Carmelita Jeter won bronze in the 100, in 11.02, behind Jamaica’s Campbell (not yet married) and another American, Lauryn Williams, both in 11.01. Jeter ran in the 4x1 relay heats; U.S. coaches opted not to use her in the final, believing a different line-up gave the Americans their best chance; the U.S. women’s 4x1 team, no Jeter, won in 41.98.

In Saturday’s prelims, the U.S. women went 42 flat, second only to Jamaica, which went a world-leading 41.84.

The U.S.: English Gardner, Allyson Felix, Jenna Prandini, Jasmine Todd.

Jamaica: Sherone Simpson, Natasha Morrison, Kerron Stewart, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce.

In the finals, the Americans put out the same line-up; the Jamaicans, Campbell-Brown, Natasha Morrison, Elaine Thompson and Fraser-Pryce.

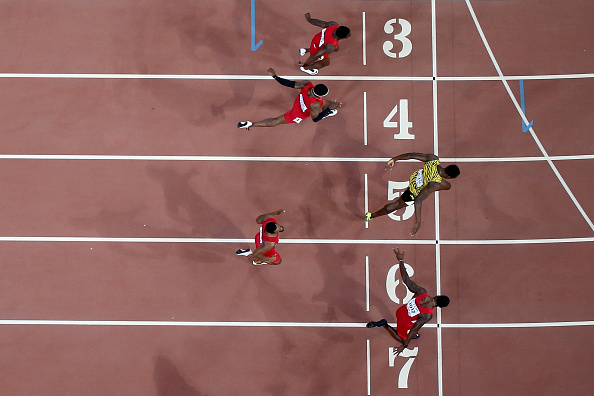

Felix ran a big second leg. But the Jamaicans had the lead by the time the stick got to Fraser-Pryce. Game over: the Jamaicans won in a world championship-record 41.07, second-fastest time in history, the Americans next in a season-best 41.68. Trinidad and Tobago pulled third, in a national-record 42.03.

On the men’s side:

At the World Relays in May in the Bahamas, the Americans figured out a formula for taking out the Jamaicans: get a big-enough lead so that even Usain Bolt, who ran anchor, couldn’t catch up. In the Bahamas, given a big lead by Justin Gatln and Tyson Gay, running legs two and three, Ryan Bailey held off Bolt for the victory.

Bailey is not here; he false started in his 100 heat at the U.S. nationals and so did not qualify; he then pulled out of the 200.

He would be missed.

In the Bahamas, the U.S. ran 37.38, and Bailey afterward made a throat-slash motion, emphasizing no fear of the Jamaicans.

The U.S. four here: Treyvon Bromell, Gatlin, Gay, Rodgers.

Jamaica in the prelims: Nesta Carter, Asafa Powell, Rasheed Dwyer, Nickel Ashmeade.

Prelim times: Jamaica 37.41, U.S. 37.91.

For the finals, the U.S. lineup stayed the same; for Jamaica, Carter, Powell, Ashmeade, Bolt.

Before it all got underway, Bolt did a little dance on the track, laughing and smiling, as always.

The Americans ran in Lane 6, Jamaicans in 4.

Inexplicably, Bromell almost missed the start; he was just settling into the blocks when the gun went off. He recovered and executed a slick pass to Gatlin, who, again, ran a huge leg two.

But the gap closed, and Bolt powered to victory in 37.36, best in the world this year.

The U.S. appeared to finished second in 37.77 despite that ugly-looking third pass, Gay to Rodgers. Rodgers actually stopped short for just a moment to try to be sure to grab the bright pink stick in the zone.

Rodgers said, "I knew that I had to slow it down a bit because I still did not have the baton. I wanted to stay in the zone."

Job not done.

More practice, more camps -- maybe more Ryan Bailey, it would appear, for 2016.

Scoreboard for the U.S. men since 2001 in the sprints: 15 races, nine fails. That's a failure rate of 60 percent.

Take out the 2001 doping matter and since 2003 it's eight fails-for-14. Still not good.

"It was very hard to get focused because of all the noise," Gay would say later, an odd thing for a veteran like him to say, adding a moment later, "We are all very upset because of the disqualification."

China, to a great roar, was moved up to second from third, in 38.01. Gatlin earlier in the week had noted the emergence of Chinese sprinters, including Bingtian Su, with a personal-best 9.99 in the 100. It was Su's 26th birthday Saturday, and after the race the crowd at the Bird's Nest serenaded him with a rousing version of "Happy Birthday."

Canada was jumped to third, 38.13.

For Bolt, this relay made for yet another championships triple -- with the exception of his false start at the Daegu 2011 worlds, and that relay in May in the Bahamas, he has won everything at a major meet, Olympics or world championships, since 2008: 100, 200 and the 4x1.

Bolt, later, on the Americans: "It is called pressure. They won the World Relays and the pressure was on them. I told you -- I am coming back here and doing my best."

Echoed Powell, "We came out very strong and I think the U.S. wanted it too bad. They made mistakes," he said, adding, "We got the stick around, and we won."