INDIANAPOLIS — For years, USA Track & Field was arguably the most dysfunctional of the major sports federations in the American Olympic scene. Personality politics ruled. Budgets stayed flat. Almost every decision seemed to be met with argument or that more basic question: what’s in it for me?

As any business or management expert would affirm, culture change is maybe the hardest thing ever.

Underway now at USATF, for anyone not stuck in the past and willing to look with more than a glancing pass, is a profound culture shift for the better.

Instead of being combative — first, last and always — USATF increasingly finds itself on the road to collaboration and cooperation.

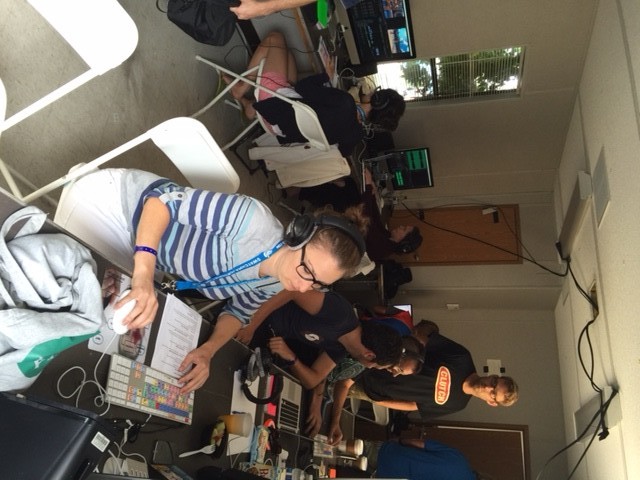

A session Saturday at an Indianapolis hotel room underscored that reality amid a master’s class in leadership from Steve Miller, the USATF board chair, and Max Siegel, the organization’s chief executive.

Siegel came dressed for the meeting in an untucked business shirt; Miller, in a black polo and black loafers with no socks. Ties and jackets? No way. Disarming? To the, well, max.

Siegel called the session Saturday a “conversation” among “key stakeholders.”

Miller said, “Together we have a chance to change the sport. Separately, we have no chance.”

At another point, Miller said, “We are in this together. We have a chance to move the organization forward. We have a chance to do some things that have never been done before. We have a chance to end the repetitiveness of the five-year, the 10-year, the 20-year conversations,” the loop that inevitably led to accusations, drama, friction and more, almost none of it constructive.

Under the direction of Siegel, chief executive since May 2012, USATF has made significant financial strides. Its 2016 budget is a projected $35 million, about double what it has been in recent years — and that is without the benefit of the roughly $500 million 23-year Nike deal, which kicks in the year after.

USATF’s logical next step: streamlining its governance.

In the wake of a meeting three weeks ago at which USATF and its Athlete Advisory Committee agreed in principle on a revenue distribution plan that will deliver $9 million in cash to athletes over the next five years, the session at Indianapolis’ Alexander Hotel was called to bring together nearly 50 people — from all over the country — to discuss “law and legislation” changes.

That is, governance.

As Duffy Mahoney, USATF’s chief of high performance, said Saturday, there’s a big difference between governance and politics.

Politics is important, of course, and grabs headlines.

Governance gets stuff done.

No one cares about governance until, actually, they do care.

The close cousin of governance is process. Process is not sexy. No one cares about process.

Again, until they do care.

Example A: the process by which the USATF board last year chose Stephanie Hightower, now the USATF president, to be the federation’s nominee to the IAAF council, the sport’s international governing body, in place of Bob Hersh, who had served for 16 years.

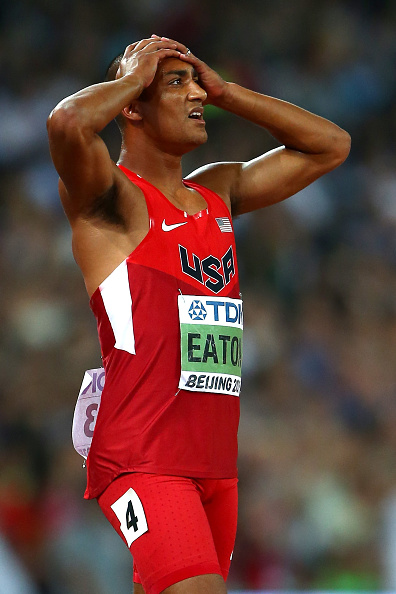

Hightower would go on in August to be the highest vote-getter at IAAF elections in Beijing.

The process, which played out at last year’s USATF annual meeting in Anaheim, California, called first for a general assembly vote.

Most importantly, though arguably not well-communicated, that vote was merely a recommendation to the USATF board of directors — who could overrule it, by two-thirds vote.

Hersh won the floor vote.

The board, though, selected Hightower, believing in her and in a new direction amid major changes coming up at the IAAF, including the election of a new president to replace Lamine Diack of Senegal, who served atop the international federation for 16 years.

In August, the IAAF picked Britain’s Seb Coe as its new president. He defeated Ukraine’s Sergei Bubka.

On Saturday, two activists spoke at length in favor of proposed rules changes -- Becca Peter, who lives near Seattle, and David Greifinger, a Santa Monica, California-based lawyer.

Greifinger returned time and again to the same theme: democracy.

"That has worked in this country for a long time," he said at one moment.

For sure.

But the United States is not a pure democracy. It is a representative democracy.

As Miller observed, "The popular vote in our country does not always elect the president."

Moreover, democracy is not the same as leadership. And what nations, companies and non-profit sports organizations such as USATF need way more of is less pure democracy -- the USOC slimmed its board down from 115 to 15, and USATF is also down to 15 from 32 and, before that, over 100 -- and more leadership.

"It's one of those things about leadership," Miller said. "You don’t get elected and [suddenly] know everything about leadership."

Nothing at Saturday’s meeting will in any way prove binding. Indeed, the entire thrust was to set the stage for this year’s annual get-together, in about five weeks in Houston.

Two proposals -- both sparked by the process that saw Hightower picked for the IAAF -- may well show up in Houston:

The first, advanced by Peter: to bar the IAAF council member from simultaneously serving as USATF president or CEO. In Saturday’s straw poll, that got two votes.

“You have to get the best person for the job,” the agent Tony Campbell said. “If the best person is wearing two hats, so be it.”

The second: to provide that the USATF general assembly elect the IAAF rep. Straw vote: one in favor.

“Why change this now?” asked Robin Brown-Beamon, the Florida-based association president. "It worked.”

To laughter in the room, Sharrieffa Barksdale, the 1984 Olympic hurdler, said, referring to Greifinger, "If you have ever seen the movie ‘Frozen,’ David — let it go!”

An even-better cultural touchstone, referred to indirectly several times by Miller: "We're all in this together," the pitch-perfect tune from the 2006 hit movie "High School Musical."

This was the theme three weeks ago, at the meeting with the athletes that led to agreement.

And that set the tone for Saturday’s get-together.

Reminding one and all that the metric that matters most is how many medals the U.S. team collects next summer at the Rio 2016 Games, Moushami Robinson, a gold medalist in the women's 4x400 relay at the Athens 2004 Olympics, said, “It’s time to move past the residue so we can get done what we need to get done.”

Added Dwight Phillips, the 2004 Olympic and four-time world long jump champion who is now chair of the Athletes’ Advisory Committee, “It has always been competitive: ‘Let’s fight, let’s fight, let’s fight.’ How about, ‘Let’s compromise, let’s come to an agreement.’ And we’ll see progress.”

To be sure, disagreement and discussion are always part of any institutional process. And that’s totally healthy.

At the same time, USATF’s long-running dysfunction, the temptation to immediately and vociferously wonder if the sky is falling, and now, often bore echoes of the same woes that for years beset the U.S. Olympic Committee — until the USOC, too, made needed governance changes (slimming down that board of directors) and putting people in place who know what they’re doing (in particular, chief executive Scott Blackmun, in early 2010).

Now it’s USATF’s turn to look forward — to acknowledge that while discussion and dissent have a place, so, too, do compromise and turning the page.

Another proposal advanced by Greifinger:

— The USATF board now numbers 15. Six are representatives of what’s called “constituent-based” groups, including youth, officials and coaches. The current reps are selected by a process that includes nominations and slates and further complications. What if those six reps were elected by their constituents?

The consensus Saturday: fine.

Even so, it was also generally agreed, whoever gets put up for any of those six slots must pass some sort of vetting. Details obviously remain to be worked out but it's common-sense they would include a background check, drug testing and, to be obvious, a passport for the international travel that track and field demands.

And this notion, put forward by Rubin Carter and Lionel Leach:

— Make the CEO “confer and agree” with volunteer leadership on a variety of decisions.

Confer? Sure, as appropriate, Siegel said.

Secure agreement? Not workable, Siegel said, to widespread assent.

How could he sign off on this deal or that if he had to secure the OK of volunteers who might -- or very well might not -- hold particular expertise?

Siegel also noted the unintended consequence of such a provision: “no accountability for my performance.” If everything had to be run by volunteers of different stripes, how in the real world to gain an accurate measure of what Siegel did, or didn't, get done?

This, of course, is exactly the move the USOC made -- away from volunteer leadership and toward empowerment of a professional CEO and staff.

Houston and the annual meeting await.

For the first time in a long time, maybe ever, the focus at USATF is not on what happened before -- the recrimination attendant to reliving and rehashing the past.

As Miller said, “We are in this together. We have a chance to move the organization forward.

“We have a chance to do some things that have never been done before," on the track and and off: "We have a chance to end the repetitiveness of the five-year, the 10-year, the 20-year conversation.”