EUGENE — Jackie Joyner-Kersee is arguably the greatest female American track and field athlete of all time. Competing across four editions of the Olympics in the long jump and the heptathlon, she won six medals, three gold. Before Max Siegel took over as chief executive of USA Track & Field, Jackie Joyner-Kersee had never — repeat, never — been invited to USATF headquarters in Indianapolis.

Let that sink in for a moment.

“I don’t want to believe the design was to leave people on the outside,” Joyner-Kersee said here amid the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials. “It was just business as usual. It became normal. You think that is the way it is supposed to be.”

Culture change is about the most difficult thing there is to effect, all the more so in the Olympic sports sphere.

At work now — in real time — is a profound culture shift for the better at USATF, which is, as Siegel put it Tuesday, both the economic engine and the governing body of track and field in the United States.

Of course there are critics, non-believers, doomsayers.

All constructive criticism is more than welcome, Siegel observing that such observations can “point out our weaknesses” and thus be “really healthy for us.” He added, “People should continue to express their criticism, their concern and hopefully their praise for the organization.”

To be sure, USATF is far from perfect. No institution is perfect. No institution can ever be perfect.

At the same time, praise where praise is due:

USATF, long the most-dysfunctional federation in the so-called U.S. “Olympic family,” has — in the four years since Siegel took over — taken concrete, demonstrative steps to become a leader in the field.

True — by virtually any metric.

Joyner-Kersee: “Change is hard. Most of the time, you don’t see change until years down the road. But there are certain things that are being put in place where, at the beginning, you might not understand why. But when the moment comes, you see it’s working out.”

For the first time in recent memory, these 2016 Trials are what they should be: a commemoration of the sport’s vibrant past as well as a well-run production at go time with an eye toward the future, in particular the 2021 world championships, back here at historic Hayward Field.

The evidence is all around Hayward, and Eugene:

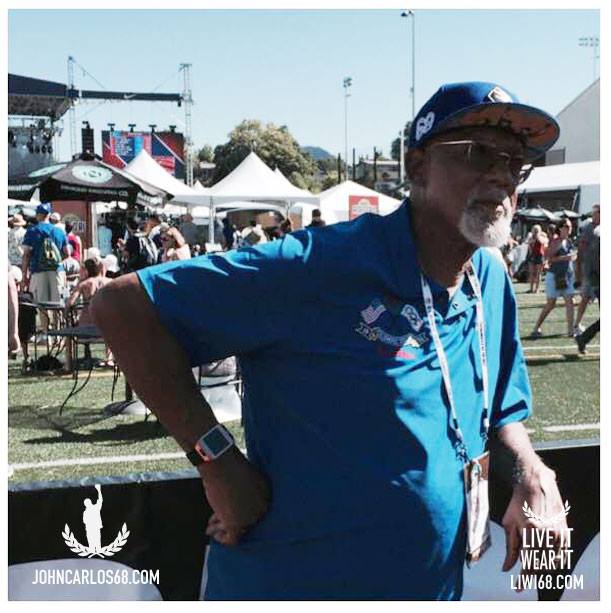

Here was John Carlos, the legend from the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, singing autographs.

Here was Adam Nelson being presented the 2004 Athens Games shot put gold medal in a Hayward ceremony. Nelson, who had initially finished second, was moved up to gold when Ukraine’s Yuri Bilonoh was, to little surprise, confirmed a doper. In 2016, Nelson got what he deserved — a ceremony before thousands cheering for him, and for competing clean. Then he went out and tried to qualify for the 2016 team, making the finals and finishing seventh. All good for a guy who on Thursday turns 41.

https://twitter.com/AdamMcNelson/status/748907838584463362

https://twitter.com/ryanmfenton/status/750129069384019968

Here, during the next-to-last lap during a prelim in the men’s 5,000, came the javelin champion Cyrus Hosteler — waving an American flag, racing exuberantly down the curve and the homestretch in the outside lane while the pack zipped by on the inside.

Here, too, behind Hayward have been hundreds, maybe thousands, of kids racing in the “little sprinters” section. Or outside the stadium — kids and grown-ups trying their luck at throwing the shot.

All of it amid the county-fair smell of kettle corn, and under brilliant blue skies.

Vin Lananna, president of TrackTown, the local organizers, who is as well the 2016 U.S. Olympic track team men's head coach, said much strategizing had gone into what he called two “common themes — bringing the athletes into close contact with the fans and introducing as many boys and girls to running, jumping and throwing as possible.”

He also said, “It is my hope that by shining a spotlight on certain events, by working hard to attract boys and girls to the sport, and by celebrating the amazing heritage of our athletes at these 2016 Olympic Trials, that we’ll really grow the awareness of today’s track and field heroes in the mind of Americans.

“And I hope that by 2021, when the world comes to Oregon for the IAAF world championships, the stars of Team USA are household names. I’m sure that on the final night of these Trials we’ll be strategizing about what next steps we can take to make that happen.”

At this point, the skeptic cries — wait. NBC sent Bob Costas to Omaha last week for the swim Trials. There Costas interviewed the stars Michael Phelps and Katie Ledecky.

Is Costas in Eugene? No.

Then again, on Sunday alone, U.S. athletes set seven world-leading marks; the hashtag “#TrackTown16” trended globally on Twitter; the USATF production team launched its first Snapchat story; and three of the five top trending items on Facebook were the U.S. track stars Allyson Felix, LaShawn Merritt and Justin Gatlin.

USATF will send a team of roughly 125 athlete to Rio, roughly a quarter of the entire U.S. delegation. Halfway through these Trials, 50 track and field athletes have been named. Of those 50, 35 are first-time Olympians. In these disciplines all three qualifiers will be first-timers: men’s and women’s 800; men’s pole vault, men’s long jump, women’s discus.

It’s all quite a change from four years ago.

Siegel had just taken over just weeks before as CEO. The 2012 Trials were marked by a bizarre dead-heat in the women’s 100 that became a worldwide source of ridicule. Plus, there was the weather.

As Siegel said Tuesday in a state-of-the-sport news conference, “It is a lot different for me. It was raining and I was in the middle of a dead heat a couple weeks on the job.”

Lots of things are indisputably a lot different.

First and foremost, USATF used to run with an annual budget of roughly $16 to $18 million. This year, it’s $36 million — the product of 17 new deals in the past 48 months, including 12 new corporate partnerships.

Has USATF figured out how to make track athletes the kind of money NFL or NBA players get?

No.

But, working in collaboration with its athletes’ council, chaired by long jump champion Dwight Phillips, for the first time an athlete who makes the U.S. national team gets $10,000 along with bonuses of up to $25,000 for Olympic gold medals. That’s all in addition to dollars that can come from the U.S. Olympic Committee.

Does that automatically make a track star a millionaire? No.

Is it a start? Yes. Just “scratching the surface,” Siegel said.

And, as Siegel pointed out, it’s reasonable to ask whether it’s fair to compare, on the one hand, track and field with, on the other, the NBA or NFL.

The pro leagues are for-profit enterprises. Moreover, they are unionized.

USATF is a not-for-profit entity. Plus, its charge is to serve not only elite athletes but also a variety of grass-roots programs.

“The conversation gets a little cloudy when people have whatever their personal definition is about sharing money with athletes,” he said. “If you host an event that gives an athlete a platform, some would say that’s not money in the athlete’s pocket. But someone needs to fund those things.”

Which leads directly to the central point.

When he took over, Siegel said, he saw two primary objectives: to effect organizational stability and to drive innovation.

Another innovation nugget: Wednesday’s hammer throw competition, to be held inside Hayward, will be available via desktop, tablet, mobile and connected TV devices. Here is the livestream link for the women's competition. And the men's.

Most important:

For the first time in maybe ever, USATF can pronounce itself stable.

Nothing — repeat, nothing — is possible without that stability, and anyone who is being reasonable would have to acknowledge that much of the criticism that attends USATF comes from those who for years have accepted intense variability as part of the landscape, often seeking to leverage that instability in the pursuit of petty politics or otherwise.

Before Siegel took over, Nelson said, “No one trusted the leadership,” adding, “When that trust is broken, a power grab goes on.”

He also said, “There is a culture change happening. There have been major changes at work at USATF in the last four years.”

Hawi Keflezeghi, the agent whose clients include Boris Berian, runner-up in the men’s 800, recently sent Siegel an email — quoted here with permission — that said, in part, “Your commitment to elite athletes through the high performance program is evident & greatly appreciated,” adding, “Thank you for all your efforts & leadership.”

Keflezighi, in an interview, said, speaking generally about the state of the sport, “If you are quick to criticize, be quick to acknowledge the good that is going on, too. Be objective enough to see it.”

Nelson, referring both to track and field generally and USATF specifically, said, “This is a family, and I genuinely mean that — even when a family fights, even when a family disagrees.

“But for a family to survive, you have to find ways to break down those barriers and re-establish communication.”

This is the key to Siegel’s style. And why USATF is on the upswing.

For students of management, he alluded to four different facets of his way in his Tuesday remarks.

One: “My style is not to discuss [in the press] things that are happening or resolutions that need to be made in the privacy of business.”

If you think that means he’s not transparent — wrong. All in, Siegel spent 50 minutes Tuesday at the lectern, half of that answering any and all questions. Beyond which, the USATF website holds the answer to almost every organizational or financial question.

Two, he and chief operating officer Renee Washington place a tremendous emphasis on — as much as possible — working collaboratively with the many stakeholders in the USATF universe.

The athlete revenue distribution — or sharing, if you like — plan?

“We worked collaboratively and painstakingly and long, and put in a collective effort with [the athlete council] … to come up with a system that was fair,” Siegel said, adding, “We continue to work in a fluid manner to improve it.”

Three, Siegel and Washington are quick to credit others.

USATF staffers, he said, “work tirelessly, are equally as passionate, care about the sport and wake up every day trying to do the best job possible.”

At Tuesday’s event, he singled out, among others in the room, Duffy Mahoney and Robert Chapman in the high performance division; and the four-time Olympian Aretha Thurmond, who has the complex job of overseeing logistics, travel and uniforms for international teams.

Too, he said, “I can not say enough about our partners at TrackTown and the city of Eugene.”

Four, Siegel can approach problems with either a macro or micro approach — whichever is, depending on the situation, most appropriate.

Micro: “We have been trying really hard to pay attention to small details that people don’t see,” he said, down to the way team uniforms get packed in the bags, with care and attention, evidence of “what it feels like to be treated with dignity and respect and the kind of importance that an athlete deserves.”

Macro: “For us as a community, for all of us who really love track and field, who would love to see the sport grow, it is not rocket science: people have to want to consume the product. You have to have people who are willing to buy tickets to the event, sponsors who are willing to spend money, people who are willing to spend merchandise.

“As a community, I would love to change the tone of our conversation. To figure out, OK — true, this is where we are falling short. But what do we do as a community to make sure that our sport is front and center with all the other properties out there?”

Change can be hard. But it can also be good. When it's right in front of your face, you just have to see which way it's pointing, Joyner-Kersee saying, “With that change, now you have athletes wanting to know: where is the office?”