Over the past two years, the World Anti-Doping Agency commissioned, in all, four independent reports that trained the spotlight on, and generated considerable controversy worldwide about, allegations of systemic doping in Russia.

Those reports cost a total of $3.7 million, according to WADA.

WADA’s 2016 annual budget totaled $29.6 million. A little math: $3.7 million over $29.6 million would amount to roughly 12.5 percent of the agency’s entire budget. Even spreading the costs out over two years leads to the same problematic conclusion: WADA, perennially cash-strapped, simply does not have that sort of money readily at hand.

In November 2015, WADA president Craig Reedie issued a call to the world’s governments to help pay for investigations.

The response underscores the complexities of reconciling talking the talk with walking the walk in the complex and nuanced world of the anti-doping campaign — where it’s easy, particularly for governments and politicians, to pay lip service to being tough on the use of illicit performance-enhancing drugs but far more problematic to do something about what, at the end, is a problem that challenges the legitimacy of sport and thus inevitably falls on sports officials to confront.

The United States government? It contributed not a penny.

The government of the United Kingdom? Likewise, not a pence.

The government of Germany, which had gone so far as to criminalize doping in sport? Nothing.

The government of Norway, where fair play and clean sport are virtually a mantra? Zero, zip, nada.

In all, WADA says, it had received by the end of 2016 a grand total of $654,903 toward that total of $3.7 million. Romania contributed $2,000. Romania!

For sure clean sport is a laudable goal.

Now the reasonable question for all who say that a level playing field is the goal:

Is this any way, figuratively speaking, to run a railroad?

—

To recap the long story of the investigations into what’s what in Russia:

The Canadian lawyer Dick Pound was asked to chair the first two independent commission reports. They focused on corruption and doping within track and field’s governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federations, or IAAF.

The two reports were released in November 2015 and January 2016.

Total cost for the pair: $1.8 million, per WADA.

The Canadian law professor Richard McLaren headed the next two independent commission reports. They addressed the wider subject of purported systemic abuse in Russia.

He delivered his first report last July. It contained terms such as “state directed oversight,” a “state-directed failsafe system” and more.

The second report was made public in December. It refers repeatedly to “institutional control,” and urged “international sport leadership to take account of what is known and contained in the [July and December] reports, use the information constructively to work together and correct what is wrong.”

Cost for the two reports: $1.9 million, per WADA.

Total, all in, four reports: $3.7 million.

Reedie, recognizing in November 2015 that WADA was looking at a monumental challenge in the months ahead, put out his call to the world’s governments.

In virtually every country but the United States, sport is an arm of a federal ministry. Governments play a key role in WADA governance. Among other things, government funding matches the monies that flow to WADA from sport, and in particular the International Olympic Committee.

Here, according to WADA, is what Reedie’s call for help has brought the agency:

|

Country

|

Payment Received From Govt(in USD)

|

Date Received

|

|

Romania

|

2,000

|

5-Jan-16

|

|

New Zealand

|

20,000

|

9-Jun-16

|

|

Canada

|

136,250

|

12-May-16

|

|

Denmark

|

100,000

|

28-Apr-16

|

|

Japan

|

187,109

|

13-Jun-16

|

|

Japan-Asia Fund

|

50,000

|

23-Dec-16

|

|

France

|

159,544

|

26-Dec-16

|

|

Total

|

654,903

|

|

|

|

|

—

When the French contribution came in the day after Christmas, WADA took note of it with a thank-you news release that said, in part, it appreciated the “tangible demonstration of France’s ongoing commitment to partner with WADA to uphold the spirit of sport.”

The agency spokesman, Ben Nichols, said in a response to an inquiry, ‘WADA is very grateful for the generous contributions made by governments from seven different countries towards our Special Investigations Fund.

“These additional funds are helping support the agency’s enhanced investigations capacity, which is an increasingly important aspect of our global anti-doping work. WADA of course welcomes and encourages any further contributions from other countries that would also be put to good use in protecting the rights of clean athletes worldwide.”

It might be noted that there are 193 member nation-states in the United Nations and 206 national Olympic committees. (The national Olympic committee of Kuwait has been suspended, in a dispute over governmental interference, since October 27, 2015.)

Seven countries contributed to the "Special Investigations Fund."

Last June, or roughly seven months after Reedie’s call for funding, U.S. Sen. John Thune, a Republican from South Dakota, chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, sent a letter to WADA asking why it had not moved more aggressively to investigate allegations of Russian doping.

The British Parliament summoned Sebastian Coe, the president of the IAAF, to give testimony in December 2015. Parliament is still in a kerfuffle over what Coe knew, didn’t know or might have known.

"The Government is fully supportive of the work of WADA and makes a significant financial contribution to their work annually, via UK Anti-Doping, to help their operational and investigative work,” a British Department for Culture, Media and Sport spokesperson said.

“Sports Minister Tracey Crouch is also one of the European members of the World Anti-Doping Agency's Foundation Board while UKAD, at the request of WADA, is working in Russia to improve their anti-doping regime."

In Norway, fairness and decency are shouted from the top of the cliffs overseeing the fjords as a way of life. There the culture ministry has responsibility for sport.

A spokesperson: “The Norwegian Ministry of Culture follows the WADA budget process closely. Our position regarding funding matters is to make sure that WADA is appropriately funded to carry out its core functions as a regulating, monitoring and supervising body. Norway contributes to WADA's activities through a yearly contribution.”

In Germany, the interior ministry oversees sport. The current minister, Thomas de Maizière, has been something of an anti-doping crusader, in 2015 taking the lead in urging passage of a new law criminalizing anti-doping and then, last summer, in urging “hard decisions and not … generosity” when it came to the Russian track and field team.

A spokeswoman, Lisa Häger, said the ministry received Reedie’s funding request on December 7, 2015.

She also said the ministry “welcomes” the WADA investigations but added:

“Nevertheless, for budget law reasons it is extremely difficult to make available a one-off payment to WADA for its investigations. Under German budget law, German government agencies may allocate funds to agencies not belonging to the federal or state administration only in the form of special allocations that are subject to strict rules and requirements. The case at hand does not really meet the conditions laid down by the legal provisions governing such allocations.

“However, under certain circumstances, the Federal Ministry of the Interior could imagine raising its yearly contribution to the WADA budget to make future investigations possible. Costs incurred by investigations should be borne by all member states since all member states benefit from the investigation results. This would also guarantee fair and transparent procedures.

“For a further debate on financing WADA and its projects, the European Union and its member states, including Germany, have asked WADA to generally discuss WADA’s priorities, core tasks and working methods. We wish to wait for the outcome of this discussion before taking a final decision.”

So which argument might most seem apt:

There’s the easy one: the tediousness of government bureaucracies?

Or the really, really easy one: the sanctimoniousness of government hypocrisy — ministers, senators and others in the public eye looking to leverage sport for easy headlines but unwilling to pay up to do the thankless but essential work it takes to keep the playing field level?

—

Or, perhaps, there is yet another way to frame this?

The United States paid $2.05 million of WADA’s $29.6 million budget. Rounding up, that’s 7 percent.

No other country is even close.

Moreover, the U.S. Olympic Committee last June approved a 24 percent funding increase to USADA. As an Associated Press story put it, the USOC chose “money over words in an effort to fix a worldwide system that [chief executive officer] Scott Blackmun says is broken.”

The move means the USOC will give USADA $4.6 million starting this year, up from $3.7 million.

The USOC and the U.S. federal government supply most of USADA’s money.

Back to WADA:

Germany and the United Kingdom paid in their 2016 negotiated shares, $772,326 apiece. Norway, too, $135,364.

It is indisputably the case that governments work months if not years ahead in the budgeting process.

It is also the case that a few years ago, when USADA went after Lance Armstrong and entourage, a matter that resulted in sanctions for roughly 20 athletes and coaches, the whole thing — including the costs of defending what turned out to be a frivolous lawsuit in U.S. federal court — ran to, and these are rough numbers, less than $500,000.

Why the discrepancy?

Because, and these are key issues going forward as well:

USADA built into its budget a contingency fund just for this sort of unexpected occurrence. WADA had no such thing.

Because of that, USADA was able to handle it at a staff level. WADA had to pay outsiders, and some of those outsiders were lawyers who, logically enough, billed at lawyer rates.

Big picture:

Asking for contributions can seem an odd way to go about seeking funding.

Did WADA ask for a defined amount from governments x or y? (No. Look at the amounts it got.)

What deadline, if any, was provided? (Seemingly open-ended.)

What justification was provided? (That is, what was the advance cost estimate for what turned out to be four investigations, and what was said about why these investigations — at least initially — could not be covered?)

Was anything said about whether a failure to contribute by a particular date would in any way impact the probe? (Seems like no.)

Back to earth: how is WADA supposed to cover, hmm, just over $3 million in unexpected costs?

—

Maybe there is yet one more way to look at these vexing complexities.

WADA is nearing its 20-year anniversary.

It has seen many accomplishments: the drafting of the world anti-doping code and the subscription to that code by virtually every sporting body and government in our world.

But, as the Russian doping crisis has made plain, the code — and, to a great extent, WADA — represent what in the United States might be called an unfunded mandate. It’s probably the same term, or a variation thereof, all around the world.

That is — an agency is asked to do something but gets little or no money to do it.

If WADA is now going to be charged with investigations, it's only reasonable to ask it internally to tighten controls. Which the agency gets -- it is now building, from the ground up, a staff investigations department.

At the same time, it’s also reasonable that it have the resource to do what it is going to be asked to do.

And there is only one reasonable source. It’s sport. In particular, the IOC.

It's not unreasonable, given that government has such a distinct role in sport in so many countries, for it to have a seat at the WADA table. As the IOC president, Thomas Bach, put it in a speech in South Korea two-plus years ago, “In the past, some have said that sport has nothing to do with politics, or they have said that sport has nothing to do with money or business. And this is just an attitude which is wrong and which we cannot afford anymore. We are living in the middle of society and that means that we have to partner up with the politicians who run this world.”

At the same time, those politicians reasonably can not be expected to give their full attention to doping in sport. They have more pressing problems: war, disease, infrastructure, economic busts and booms and on and on and on.

Besides, when they do turn to sport, they can come up with horrifying discrepancies.

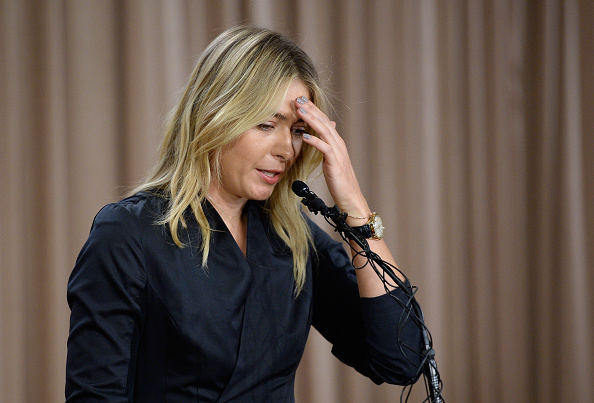

The tennis player Maria Sharapova will return to competition April 26 in Stuttgart. She will have served 15 months off after her two-year doping ban for meldonium, the Latvian heart-attack medicine, was cut by nine months by a sports court that found she had no intent to cheat. Note: this is sport dealing with a sport matter.

Compare: Girmay Birahun, a little-known 22-year-old Ethiopian marathon runner, is now facing at least three years in an Ethiopian prison after testing positive for — meldonium.

Ethiopia, like Germany, criminalized sports doping. This is government dealing with a sport matter.

“I don’t want to support people who have this evil in them,” Haile Gebrselassie, the distance running great who is now head of the country’s track and field federation, told the Independent, a British newspaper, adding a moment later, “Thanks to the government, we also have prison available as a punishment.”

He also said, “In a way I am scared for the athlete, sad for him, for what he will face in jail. Three years minimum, That’s a very bad punishment for someone to face. He will be the first Ethiopian athlete to go to jail and he has been crying non-stop ever since. But I need to work to protect the majority, not the individual.”

Fairness demands the level playing field that so many in so many places pay lip service to.

Talk is cheap. Action takes real money. There’s only one institution that has that real money, and that’s the IOC, flush with broadcast and sponsor revenues.

This, from page 134 of the IOC's most recent annual report, for 2015:

"For the 2013-2016 Olympiad, the IOC is on track to realize a USD 5.6 billion total revenue target, which would allow it to achieve the overall objective of 90 percent distribution to support the development of sport worldwide.”

Somewhere in that $5.6 billion — again, $5.6 billion, with a b — there is money to fund an anti-doping system that works.

Because about this there can be no argument: ladies and gentlemen, we all get what we pay for.