The 44th president of the United States ends his term this week, succeeded by the 45th, and in a ceremony Monday at the White House honoring Major League Baseball's 2016 World Series champions, the Chicago Cubs, Barack Obama proved his usual eloquent self in describing sport’s distinct role in American — indeed, global — society.

What’s now up to history to judge when it comes to sport is the demonstrable disconnect between Mr. Obama’s eloquence and his actions. Arguably no president in American history, none all the way back to George Washington, has been as disruptive as Mr. Obama.

Particularly in the sphere of international sport.

There can be no question, none whatsoever, that Mr. Obama talks a good game. On Monday, for instance, in the august East Room of the White House, jammed with dignitaries and Cubs fans alike, many in jerseys and caps, the president was funny, captivating, moving and profound, all of it, in a 20-minute address.

Referring to his campaign slogan in 2008 and the Cubs’ World Series drought, which would ultimately extend to 108 years before the Cubs last fall defeated the Cleveland Indians in seven games, Mr. Obama said Monday: “… Even I was not crazy enough to suggest that during these eight years we would see the Cubs win the World Series. But I did say that there's never been anything false about hope.

Everyone laughed and applauded as he added, “Hope — the audacity of hope.”

The president, a longtime fan of the Chicago White Sox, the 2005 World Series champs from the city's South Side, went on to say:

“All you had to know about this team was encapsulated in that one moment in Game 5,” meaning the World Series, “down three games to one, do or die, in front of the home fans when [the catcher] David Ross and [the pitcher] Jon Lester turned to each other and said, “I love you, man." And he said, "I love you, too.” It was sort of like an Obama-Biden moment,” a reference to the vice president, Joseph Biden, Jr.

Later, referring to the Cubs’ victory parade: “Two days later, millions of people -- the largest gathering of Americans that I know of in Chicago. And for a moment, our hometown becomes the very definition of joy.”

And, finally:

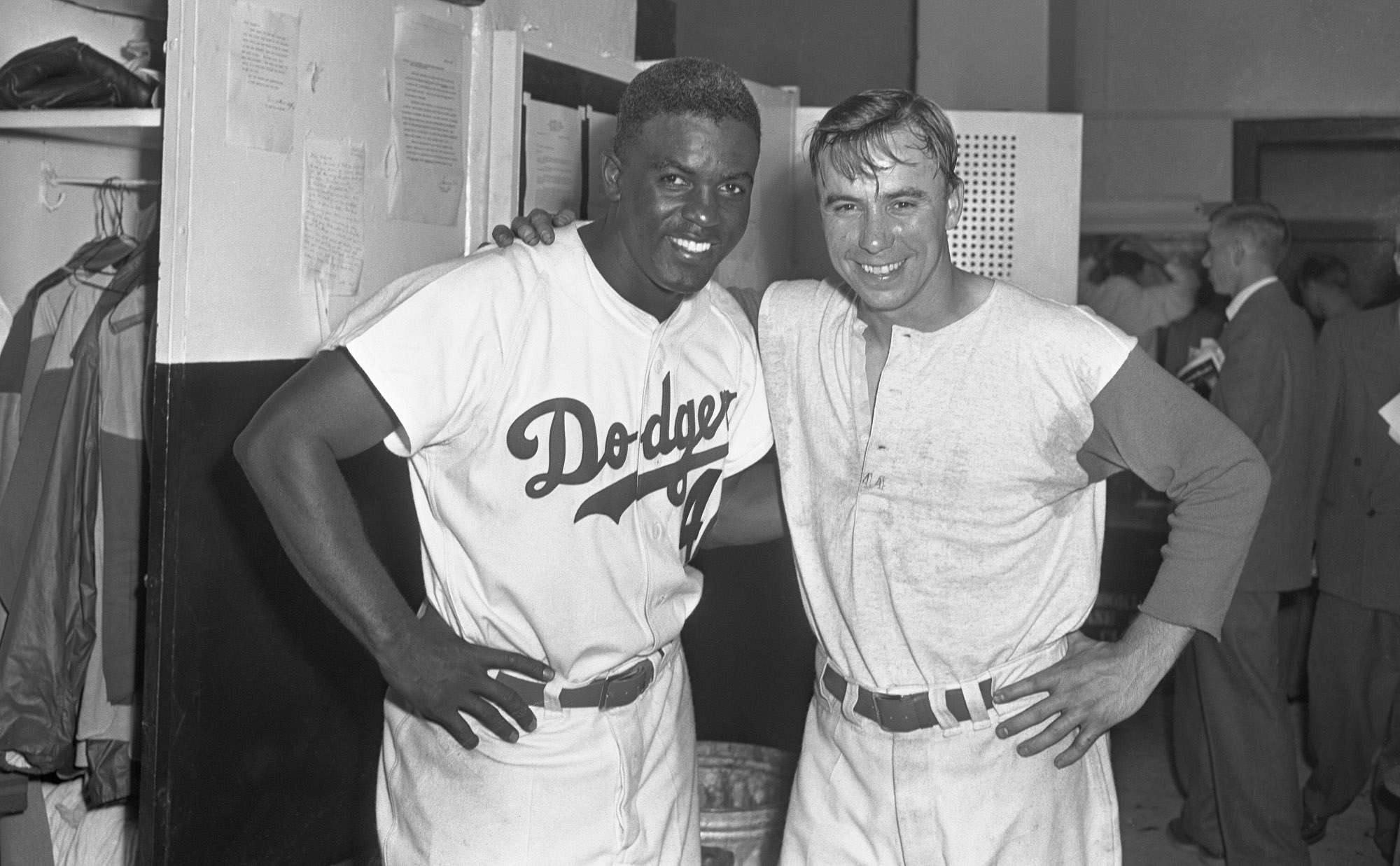

“So just to wrap up, today is, I think, our last official event — isn’t it? — at the White House under my presidency. And it also happens to be a day that we celebrate one of the great Americans of all time, Martin Luther King, Jr. And later, as soon as we're done here, Michelle and I are going to go over and do a service project, which is what we do every year to honor Dr. King. And it is worth remembering — because sometimes people wonder, well, why are you spending time on sports, there's other stuff going on — that throughout our history, sports has had this power to bring us together, even when the country is divided. Sports has changed attitudes and culture in ways that seem subtle but that ultimately made us think differently about ourselves and who we were. It is a game and it is celebration, but there's a direct line between Jackie Robinson,” the first African-American major league baseball player with the Brooklyn Dodgers, in 1947, “and me standing here. There's a direct line between people loving Ernie Banks,” the Cubs star from 1953-71, “and the city being able to come together and work together in one spirit.

“I was in my hometown of Chicago on Tuesday, for my farewell address, and I said, ‘Sometimes it's not enough just to change the laws, you’ve got to change hearts.’ And sports has a way, sometimes, of changing hearts in a way that politics or business doesn’t. And sometimes it's just a matter of us being able to escape and relax from the difficulties of our days, but sometimes it also speaks to something better in us. And when you see this group of folks of different shades and different backgrounds, and coming from different communities and neighborhoods all across the country, and then playing as one team and playing the right way, and celebrating each other and being joyous in that, that tells us a little something about what America is and what America can be.

“So it is entirely appropriate that we celebrate the Cubs today, here in this White House, on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s birthday because it helps direct us in terms of what this country has been and what it can be in the future."

These are, genuinely, lovely and moving sentiments. Thank you, Mr. President.

Did Mr. Obama’s administration prove true to those sentiments?

During most of his two terms, it can be argued, Mr. Obama — or by way of extension, deputies in his executive branch — used sports to project the full power and authority of the United States, both by way of action and, in the case of the president himself, omission. The government ranged far afield in projecting distinctly American notions of equality and morality in sports, some of the very values Mr. Obama said Monday "America can be," though it remains far from clear the roughly 200 other nations in the world can or should be like the United States, or want to be. The U.S. government pushed its views of the law in the anti-doping arena. And, of course, though there had been no cry to do so, the U.S. government saw fit to deputize itself to police international soccer.

Was this all triggered by the International Olympic Committee’s emphatic rejection of Mr. Obama in 2009?

Recently having been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the president went to Copenhagen that October to lobby for Chicago, his hometown, then bidding for the 2016 Summer Games. Chicago failed to make it out of the first round, fourth of four, losing to Rio. Madrid and Tokyo were also in the race.

"Other than people who like to cheer, 'We're No. 4! We're No. 4!' I don't know how this is anything but really embarrassing," Republican strategist Rich Galen told CNN at the time, adding that Obama's failed pitch would “probably be the joke on Capitol Hill for weeks to come.”

Had Mr. Obama ever before suffered a defeat, indeed a rejection, so intense and so personal? Was it that Mr. Obama was himself stung? Or was it his longtime, and protective, aide, Valerie Jarrett? Or both? Or others in the president's close circle as well?

Seven-plus years ago, the president played off Chicago’s Olympic loss. He said it was “always a worthwhile endeavor to promote and boost the United States.”

His real feelings may have emerged in an interview published this past October in New York magazine:

“So we fly out there. Subsequently, I think we’ve learned that [the] IOC’s decisions are similar to FIFA’s decisions: a little bit cooked. We didn’t even make the first cut, despite the fact that, by all the objective metrics, the American bid was the best.”

As anyone who has spent the better part of a lifetime in politics can attest, “objective metrics” often mean nothing. Same for just four hours around the IOC, which is how long Mr. Obama was on the ground in Copenhagen that October morning. How could the president of the United States not have known that?

And what has been the fallout since?

— 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016: Olympics, Winter and Summer. Four editions of the Olympics during Mr. Obama's two terms, four opportunities to make an appearance, two — in Canada in 2010, the United Kingdom in 2012 — in countries as close and friendly to American interests as they might get, hockey rivalries or words like “trunk” and “boot” aside. Mr. Obama shows in none of the four. (Michelle Obama went to London.) Compare: President Bush attended the 2002 Salt Lake and 2008 Beijing Games. President Clinton made the 1996 Atlanta and Hillary Clinton the 1994 Lillehammer Games.

— September 2013: Thomas Bach is elected IOC president. Since, Mr. Bach has met more than 100 heads of government and state. But not Mr. Obama. In October 2015, Mr. Bach and most everyone in senior Olympic leadership traveled to Washington for a conference. Mr. Obama did not deem it worthy of his time. Late in the event, Mr. Biden — clearly pressured to show up on behalf of the administration — made a seven-minute cameo.

— February 2014: Mr. Obama, in response to a Russian anti-gay propaganda law, decides to try to stick it to his friends in the Kremlin by sending to the Sochi Games U.S. delegations for the opening and closing ceremonies that include a number of gay athletes, including the tennis star Billie Jean King. Why a tennis star, even one as superlative as Ms. King, ought to be featured at a Winter Games event is yet to be explained.

Mr. Bach said in opening the Sochi Olympics, in a shot at Mr. Obama, “Have the courage to address your disagreements in a peaceful, direct political dialogue and not on the back of the athletes.”

— 2015, FIFA indictments. This is not to say that there wasn’t wrongdoing on multiple levels in and around the international soccer scene. The relevant question for history is otherwise. Outside the World Cup, soccer is far from baseball, basketball and especially football in the United States. And by far the majority of those accused have not been American citizens. The Justice Department, when it brings an explosive case such as this, does so to score political points as much to make a case in court. So: why so important for the FBI, IRS and the Attorney General of the United States herself to make this a federal matter?

— May 2016: federal prosecutors in Brooklyn, from the U.S. Attorney’s office serving what’s called the Eastern District of New York, have opened an investigation into allegations of doping by top Russian athletes, the New York Times reports. For those keeping score at home: Loretta Lynch, the attorney general, used to head that Brooklyn office. For those further keeping score: this is the same Justice Department that brought cases sparked by allegations of doping against the likes of baseball stars Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds, couldn’t seal the deal, but now believes considerable taxpayer resource is well spent pursuing Russians?

President-elect Donald Trump, meanwhile, has already spoken by phone with Mr. Bach, expressing support for the Los Angeles bid for the 2024 Games. Paris and Budapest are also in the race. The IOC will pick the 2024 site in September at an assembly in Lima, Peru.

Mr. Trump takes office on Friday. For sure, he has a range of priorities to pick from. If he decides that one of them is making new friends, and fast, in international sports, he could make it plain to his pick for attorney general, the current U.S. senator Jeff Sessions, the Republican from Alabama, that the Brooklyn investigation ought to be dropped, and fast.

Like, why is the United States government interested in doping by Russian athletes?

Especially an administration directed by Mr. Trump, who has shown little to less than zero interest in pursuing allegations the Russians might have played an active role in pre-election hacking?

Mr. Trump wasn’t at the White House Monday. Not his moment. But in the Ricketts family, which owns the Cubs, here nonetheless was a little slice of America as it is right now: Todd Ricketts, Mr. Trump's pick for deputy commerce secretary, stood to one side of Mr. Obama while on the other stood Mr. Ricketts' sister, Laura, who during the campaign raised significant funds for Mrs. Clinton.

This past summer, as he was heading off to vacation at Martha’s Vineyard, the remote Cape Cod locale, Mr. Obama, with a nod to Mr. Trump, had this to say as the Rio Games were just about to get underway:

“In a season of intense politics, let’s cherish this opportunity to come together around one flag.”

And:

“In a time of challenge around the world, let’s appreciate the peaceful competition and sportsmanship we’ll see, the hugs and high-fives and the empathy and understanding between rivals who know we share a common humanity.”

Beautiful words. But — just that. Just words.