We live now in such a sound-bite society. Too, we swim in a culture in which everyone wants answers, a definitive result, the end of the story — right now.

Particularly when it comes to matters involving doping and entourage.

Sorry, everyone. That’s not the way the real world works.

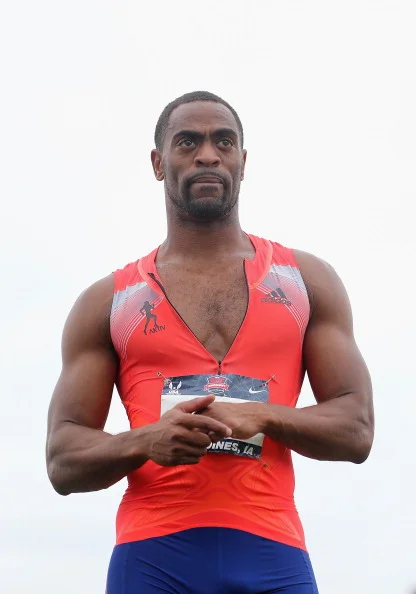

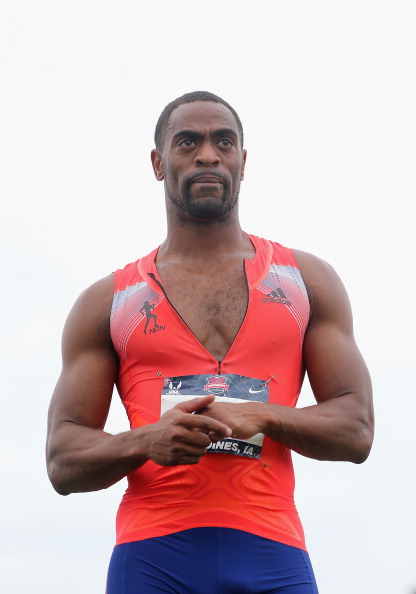

The first burst of news coverage has now come and gone involving Tyson Gay, the American record-holder in the 100-meter dash and, to be honest, almost all of it was enough to make you wonder why anyone would voluntarily come clean.

Gay’s case rightfully ought to be seen through a different lens.

It ought to be viewed as part of a larger, more comprehensive move by authorities, in particular the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, to learn and then use what an athlete knows to try to break the circle of doping — by going after, if applicable, coaches, trainers, managers, agents, doctors, other athletes, whoever.

In this case the athlete happened to be one of the biggest names in the biggest sport in the Olympic movement.

As Gay said when he was first busted, “I basically put my trust in someone and I was let down.”

David Epstein, in a story co-published with ProPublica and Sports Illustrated, has reported that Gay tested positive — he failed three tests — for a steroid or steroid precursor believed to have come from a cream given to him by Atlanta chiropractor and “anti-aging specialist” Clayton Gibson III.

But — assuming all that is true, and Epstein has consistently proven a first-rate reporter — Gay didn’t just pick up the phone and call Gibson. There’s way more to the story. That’s what Gay has now told USADA: everything else.

The USADA news release notes, in the specific language of the World Anti-Doping Code, that Gay provided “substantial assistance.”

The way USADA works, you can be sure there were multiple meetings. There were documents. There were products.

We will learn about all the rest of those connections. Be sure there are those who have traveled in track and field circles — and perhaps not just in the United States — who ought to be plenty anxious.

Draw your own conclusions but, typically, in these sorts of things government authorities know now what’s what. Obviously, these agencies never announce who they might be inquiring about, or what timetables might be at issue.

To get through all of this takes time. It takes process.

What we got, instead, were headlines like these:

Bleacher Report, atop a Bleacher-written story: “Tyson Gay Suspended for 1 Year Following Failed Drug Test”

Huffington Post, atop an Associated Press account: “U.S. Sprinter Tyson Gay Returns 2012 Olympic Medal After Positive Drug Test”

Both these headlines: factually correct.

The headlines, and the accompanying stories, totally glossed over the larger, and more relevant — the more important — point.

Why was Tyson Gay only getting one year?

A standard doping ban is two years, at least through the end of 2014, until the new World Anti-Doping Agency rules take effect and a standard ban goes up to four.

Gay got half that two. He got one.

Frankly, the news coverage — and the response it provoked on social media — did Gay, USADA and, now, WADA, the IAAF and the International Olympic Committee a disservice.

Because now the entire case is politically charged, and for what?

We get swimmers like Britain’s Michael Jamieson, who won a silver medal in the men’s 200-meter breaststroke in London in 2012, tweeting,

...& is only banned for 1 year, backdated - so he's eligible to compete from next month. Testosterone isn't taken by mistake. National...

— Michael Jamieson (@mj88live) May 3, 2014

...governing bodies have too much say in the length of suspension. This story lets us know that there is no real desire to tackle doping!

— Michael Jamieson (@mj88live) May 3, 2014

Mr. Jamieson — to deconstruct, sir, picking up with the word "National":

The entire point of the USADA and WADA system, just as it is your country, is to take governing bodies such as USA Track & Field out of the process. USATF had nothing — repeat, nothing — to do with any part of this investigation or the one-year ban.

As for that next sentence, you are absolutely entitled to your opinion. And that opinion is ridiculous. To ask the obvious: what first-hand knowledge of Mr. Gay’s case did you have before rendering that judgment?

The reason to ask is that the Daily Mail, the English newspaper, cited you in the story as part of what it called a "furious backlash from athletes" in the headline. The story also went on to quote Sebastian Coe, the London 2012 chair who is a leading candidate to become the next president of the IAAF, track and field’s governing body: “There has to be confidence that the athletes on the track know they will be treated in exactly the same way, and spectators must have complete confidence in knowing what they are watching is legitimate.”

Actually, for sure spectators must have complete confidence in knowing what they are watching is legitimate. That, to be frank, is track and field’s ongoing credibility problem, as absolutely Lord Coe knows well.

But there is no justification for treating everyone the same way. None whatsoever. The rules now allow that if you provide “substantial assistance,” you get a break, plain and simple, as Lord Coe surely knows as well.

What we may now see is Gay’s case appealed. In such cases, the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport gets the final word. Which means time and money. If that happens, what justice is being served?

Is Gay well-served? USADA? Who, exactly?

It’s ironic, really. In the Lance Armstrong case, USADA is accused of being the ultimate witch-hunter. Here Gay gets a year, and USADA is accused of being too lenient. What, it’s damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t?

This is precisely the crux of the problem with the sound-bite, rush-to-judgment nature of where we are.

Now we get comparisons between Gay’s 12 months and the 18 months Jamaican sprinter Asafa Powell — another big name — got for a supplement with a banned stimulant. (Query: did Powell provide "substantial assistance"? The answer is obvious.)

Yes, for sure, as a corollary matter, it’s interesting and intriguing to try to figure out whether the others on that 2012 U.S silver medal-winning relay team will get to keep their medals — but this is an issue on which the IOC and CAS have gone different ways, given individual fact patterns, in recent years.

It’s a further irony that Justin Gatlin ran on that relay, and he, too, has served a doping ban.

But, again, that’s not the central point.

The key element in the USADA news release, as well as the increased big-picture focus in the anti-doping campaign, is the focus now on the entourage.

Indeed, a new feature of the Code, taking effect at the start of 2015 — just to show how determined WADA is about trying to shake things up — makes it an anti-doping violation for an athlete to associate with an “athlete support person” if the athlete has been formally warned specifically not to do so.

WADA and other anti-doping authorities have learned that athletes typically don’t just go online and order up a mess of steroids; or sketch out a calendar with cycles for usage of substance A, B or C; or intuitively know how to stack steroids X, Y or Z with EPO. These things take money and expertise.

To borrow from the saying: it takes a village. Many successful athletes have a kind of “village” around them. What 15 or so years of the WADA-focused anti-doping campaign has taught is that it is not enough to just go after the athlete, him or herself. You have to disrupt the enablers in that “village” as well, or the status is likely to remain quo.

Back to last Friday’s release: “For providing substantial assistance to USADA; Gay was eligible for up to a three-quarter reduction of the otherwise applicable two-year sanction under the Code (or a six-month suspension).”

Again, Gay’s time could have been cut down to just six months from two years. He got a full year. Does that sound like total leniency?

Just so everyone understands: had this case come up next year, given the WADA Code that goes into effect this coming Jan. 1, given the “substantial assistance” Gay provided, he might well have walked away with no time.

So — here is the deal, literally and figuratively:

Tyson Gay decided to cooperate. Because of that, all athletes, and for that matter, everyone with an interest in clean sport, got a two-for-one. He gave back his unclean medal from London. And now USADA — and, presumably, others — get to go after the entourage.

Gay's one-year period of ineligibility runs for a year from June 23, 2013, the day his sample was collected at the USA outdoor nationals. Obviously he passed whatever tests there were in London, or we would have known about it; USADA had no evidence of his misconduct from July 15, 2012, the date the release says he first used a product that contained a prohibited substance, until he came forward.

For those who prefer:

One way of looking at his ban -- now that he has voluntarily given back his London 2012 medals -- is that it is in effect like two years, from July, 2012, through June, 2014. He didn't just give back that relay medal; he also forfeited all medals, points and prizes from July 15, 2012, forward. Don't forget that at those same USA 2013 nationals Gay ran a 9.75 100.

Gay said in an interview Saturday with his hometown paper, the Lexington, Ky., Herald-Leader, “There’s a lot for me to tell, my side …”

In time we will all hear it.

Everyone just be patient. Sometimes — a lot of times, actually — that’s the way the real world works.