MILAN — Thomas Bach famously said, change or be changed.

That mantra is now on the doorstep of the new International Olympic Committee president, Kirsty Coventry.

IOC president Kirsty Coventry at the IOC session

The Milano-Cortina Winter Games open Friday. Since 2019, when the Italians won the Games, the project has been one cluster after another. Cluster being half a word. Those who can will recall Torino in 2006. It feels like déjà vu all over again with this added bonus for skeptics — can they even sell out the 2026 opening ceremony at the iconic San Siro stadium? Recently announced: a 2-for-1 ticket package for fans 26 and under.

Seen Thursday in Milan: like, please, come to the opening ceremony

Organizers put out a statement that said, “Being there means experiencing the greatest live show in the world, sharing an unforgettable emotion and becoming part of a moment that will remain in collective memory forever.”

You have to upsell the opening ceremony? Really?

Lights out Wednesday at curling

On Wednesday, five minutes into the first event of the 2026 Games, a curling match, the lights went out.

Giovanni Malago, head of the organizing committee, told the IOC earlier this week at the organization’s assembly, “The journey has lasted almost seven years and it has not been without hardships and obstacles.”

Perhaps the Milano-Cortina Games will prove a welcome distraction. The IOC could use it. There are challenges aplenty, which the “greatest live show in the world” will for many distract. But they assuredly are there: with the IOC administration and with commercial realities that now seem to be - to use a phrase - the new norm.

The Bach era has left massive, fixed overheads in both Lausanne, where the IOC is based, and in Madrid, headquarters of Olympic broadcasting.

That overhead burdens funds that could — arguably should — be available to core stakeholders, including the international federations. Oh, and the athletes.

Moreover, it presents a difficult human resources management challenge — especially when one looks at the salaries of the IOC directors, readily available at ProPublic and dissected in detail by the German journalist Jens Weinreich at his site, The Inquisitor.

As Weinreich noted, over the 2021-2024 Olympic cycle, the IOC directors collectively got paid more than $55 million. That’s more than the top federations got from their chunk of IOC cash. For both the Tokyo and Rio cycles, World Athletics got $39.48 million.

Weinreich also noted that in its 2014 financial report — Bach was elected in September 2013 — the IOC listed 475 full-time employees in Lausanne. The latest sustainability report, as he reported and as you can see on page 13 here, counts 778 in Lausanne and 265 in Madrid.

What this means is plain: you’ve got directors with enormous salary increases along with massive growth underneath.

On the surface, Coventry’s “pause and reflect” appears to focus on the concerns of the 100 or so IOC members, including their role in host city elections and the timing and process for selecting host cities.

Too, the evolution of the Olympic program — that is, what sports are included at each edition of the Games. Hello, breakdancing, (regrettably, because it never got a fair shake) goodbye.

The reasonable question is whether this is, as the old saying goes, just putting lipstick on the pig.

To be way more polite about it: Coventry, in a news conference at the end of the assembly, said the IOC is “at a pivoting point.”

The challenges with both the Olympic business model and the human resources culture now seem to be surfacing at multiple levels and at a rapid pace in Lausanne. That would suggest symptoms of way bigger issues:

Is the Olympic business model still right?

Does the IOC need so many people?

Is the Bach approach — centralizing authority within the staff — now institutionalized in IOC DNA? To what effect?

Further, and significantly, is the commercial relationship between the IOC’s top-tier sponsor program, which goes by the acronym TOP, and organizing committees?

By effectively corporatizing the IOC administration —overlaid on top, word used deliberately, of an aging Olympic commercial model — it’s clear there are cracks at many levels.

It was only a year or so ago, in the lead-up to Coventry’s first-ballot election in March, that sponsors were said to be lining up to become new TOP partners.

Really? Where are they? Who, for instance, will replace Toyota?

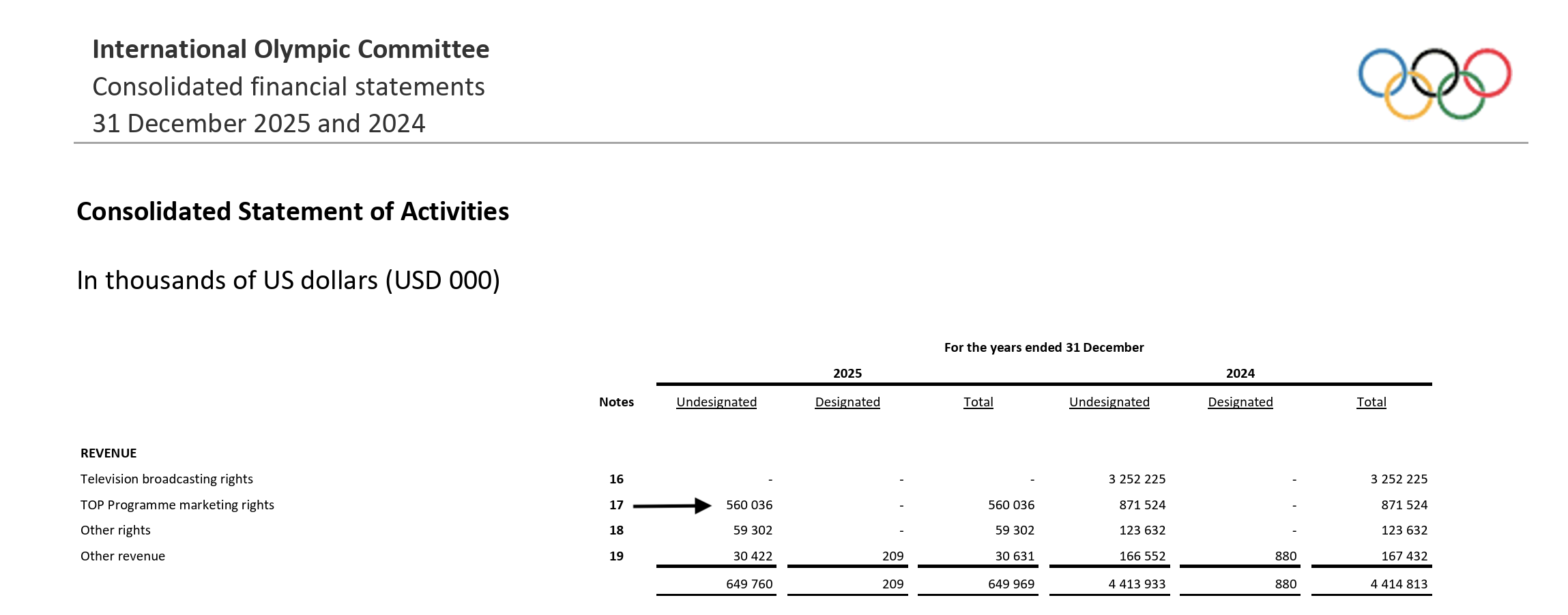

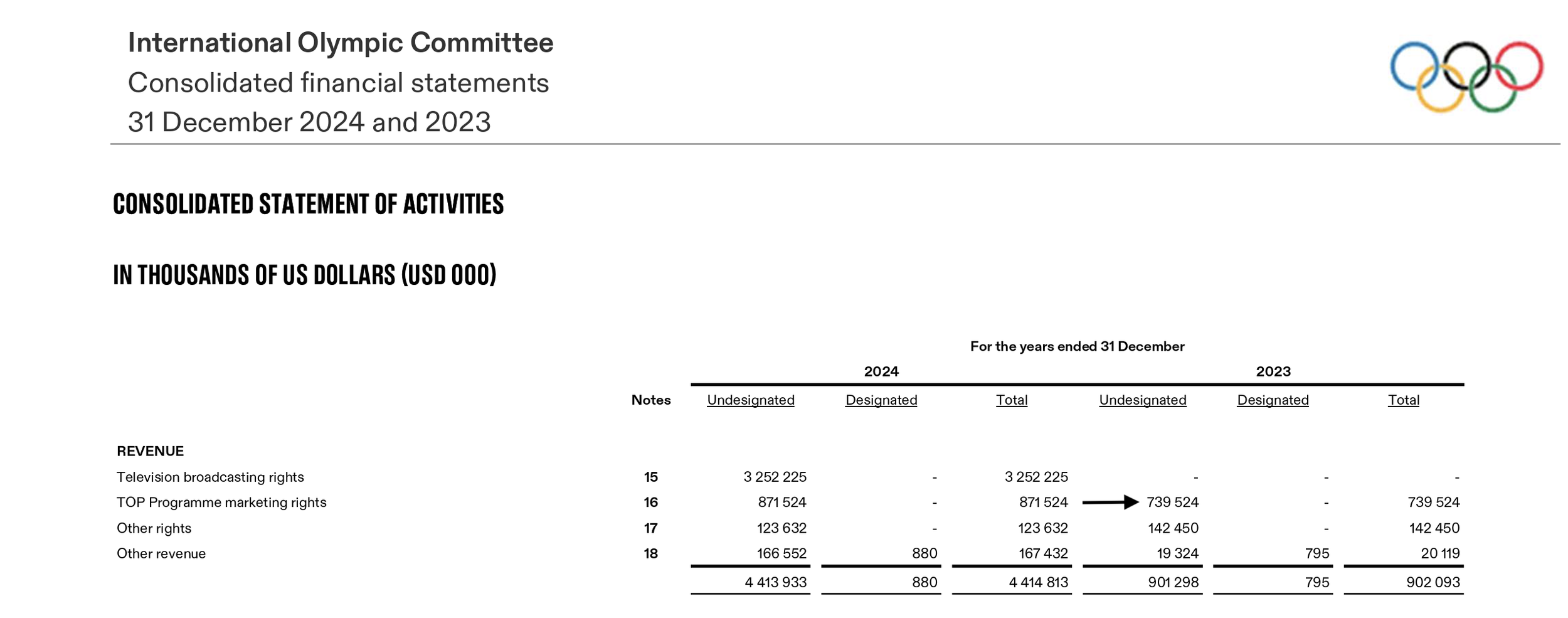

The IOC financial statements, which dropped Tuesday on Day One of the assembly in Milano, are particularly telling.

In 2025, the IOC brought in $560 million in TOP revenues. Compare: $871.5 million in 2024. That’s a drop of $311.5 million.

At the end of 2024, along with Toyota, the IOC lost Atos, Bridgestone, Intel and Panasonic.

Of course, 2024 was an Olympic year. Let’s compare the numbers for 2023, like 2025 a non-Olympic year.

To make it easy: $871.5 million in 2024.

In 2023: $739.5 million.

So: in 2025, the year after the purportedly phenomenal Paris Games, the IOC took in $179 million less than in 2023. Say what?

In October, Coventry, citing mutual consent, killed the deal with Saudi Arabia around esports. Bach had promoted this deal.

Whatever that deal was worth, and one hears unverifiable but crazy numbers, it obviously hit Olympic cash flow, and hard. Whatever was expected from this transaction has — evaporated.

To be fair, the accounts made public Tuesday at the IOC assembly purport to paint a rosy picture — assets of $7 billion against liabilities of $$2.1 billion.

Reality check: much of the wash-up of the TOP exit will not hit the bottom line for a couple more years.

Turing to the stakeholders, in particular the athletes, the remaining TOP sponsors, the host cities, the federations, broadcasters and the International Paralympic Committee: the shrewd among them will be paying keen attention to the push by Italian prosecutors in Milan to challenge the governance structure of Games organizing committees.

The question is whether what might have made sense years ago is no longer fit for purpose under the new, corporatized IOC, particularly when measured against transparency demands.

We now have two editions of the Games where investigations into procurement and price testing of services, some provided directly by the IOC, are — arguably rightly — under the microscope.

In Tokyo this led to criminal action against Dentsu, in connection with a scheme to rig bids for lucrative contracts to operate test events and competitions for the 2020 Games (held of course in 2021).

Again, to be fair: no one at the IOC was implicated.

This, though, only raises the obvious question, given the IOC’s significant oversight, increasingly hands-on, of each and every organizing committee:

Was the IOC aware of any problems in Tokyo? If not, doesn’t that suggest the IOC system of oversight would be, to be generous, far from adequate?

Meantime, the IOC now exclusively provides what are called Games Learning and Knowledge services to these organizing committees. It costs a lot of money: said to be $86 million, more or less, for the Winter Games, $125 million for the Summer Olympics.

A winning city must sign what’s called a host-city contract.

Typically, that moment is all jubilation for the new organizers. Do they have the time or opportunity for external price testing — or is that necessarily limited?

That kind of learning and knowledge outlay should be viewed with considerable skepticism — particularly given the central overhead costs that increased sharply in Lausanne and Madrid during the Bach years, and the IOC’s much-touted commitment that no more than 10% of Olympic TOP and broadcast revenues go toward administration.

Bottom-line: what is an organizing committee getting for $125 million?

This is just one example. The other is a profile change in the TOP sponsors, most notably the inclusion of a global management consulting category held by Deloitte.

This is what has attracted the attention of Italian prosecutors, particularly a 2023 contract awarded to Deloitte — part of a broader investigation into alleged bid rigging and corruption involving IT and digital services contracts for the Winter Games.

Deloitte is the IOC TOP technology partner.

When sponsors pay all their revenue to the IOC centrally and are, in effect, the official suppliers — via services, not goods — to the organizing committees, it is obvious there’s a natural temptation to recover as much as possible.

Also, given the influence the IOC has on organizing committee staff at various levels, it is the farthest thing from a big jump for staff to be considered compromised —to please the IOC, who, for some if not many, will dictate their careers post-Games.

One solution may be to separate sponsorship and service.

That is, if you are an IOC TOP sponsor, then you ought not to be able to provide services to the Games.

This would quickly test the motivation of Deloitte and others in such services categories.

Also this: perhaps the Italian prosecutors, as the FBI with FIFA some years ago, should seek the assistance of Swiss authorities to better understand what is really going on with questions when it comes to allegations of potential RFP rigging and what — again, seeking to be scrupulously fair — the IOC administration knew, or did not.

There seems little doubt the IOC business model needs updating for 2026 and beyond. And, rightly, to meet the bar for transparency set by taxpayers — in most nations, the ultimate underwriters of a Games.’

For Coventry, what then of “pause and reflect”?

As the president said when opening the IOC assembly, it’s time for “uncomfortable” conversations.