For nearly a dozen years, speculation has swirled that Lance Armstrong failed at least one doping test at the 2001 Tour of Switzerland, in particular for the blood-boosting drug erythropoietin, or EPO.

Even as Armstrong has in recent months acknowledged the serial doping that won him seven straight Tour de France championships from 1999 to 2005, the matter of the 2001 Tour of Switzerland has remained contentious.

Anti-doping officials have made plain their assertion Armstrong’s tests were “suspicious” for EPO. Many have wondered if there was a cover-up. Leaders from cycling’s international governing body, which goes by the acronym UCI, have said there was nothing to cover-up because Armstrong never tested positive.

Now, finally:

During the 2001 Tour of Switzerland, according to the lab reports themselves, Armstrong never tested positive.

At the same time, two of his samples were, indeed, categorized as “highly suspicious.” But after extensive testing – all of it conducted in the summer of 2001 – neither met the standard to be formally declared positive.

The lab results are included with a five-page letter sent Thursday from UCI president Pat McQuaid to World Anti-Doping Agency director general David Howman. USADA, copied on the letter, concerned with what it called “numerous inaccuracies and misstatements,” issued a seven-page response on Friday, signed by general counsel William Bock III.

Both letters, now circulating in the international sports community, were obtained by 3 Wire Sports.

In the UCI letter, McQuaid asserts the lengthy explanation and the documents themselves “finally puts pay to the completely untrue allegations” of a positive 2001 test and “any subsequent cover-up by the UCI.”

For the UCI, it must be understood, this is a – if not the – key point: no cover-up.

To emphasize that point, McQuaid says the UCI would be “very grateful” if WADA or USADA would make a public statement “confirming the information in this letter,” keeping in mind the “great damage” done to UCI’s reputation “by these false and scurrilous allegations.”

The USADA response: if UCI officials had “strong evidence” way back in 2001 that Armstrong was using synthetic EPO, why didn’t they do something about it then?

To that end, the USADA reply includes a “short list” of 10 “new concerns” and a request for seven buckets of new information relating to Armstrong tests for the years 1999-2010.

Its letter asserts the documents the UCI turned over were “quite incomplete” but also says, “USADA is thankful that the UCI has now belatedly come around to USADA’s position that it is appropriate for the UCI to share with USADA and others in the sports world Mr. Armstrong’s test results.”

As recited in the USADA “Reasoned Decision,” issued last October, which sets forth in detail Armstrong’s pattern of doping, the 2001 Tour of Switzerland – a warm-up for the Tour de France – took place from June 19-28.

Armstrong won the event.

Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis, both former Armstrong lieutenants, provided USADA with affidavits. Armstrong said or implied he had tested positive in the Swiss race but had been able to “make the EPO test result go away,” according to USADA’s case.

Armstrong’s conversation with Hamilton was in 2001, with Landis in 2002. Landis recalled Armstrong saying he and team leader Johan Bruyneel “flew to the UCI headquarters and made a financial agreement to keep the positive test hidden.”

It has long been public knowledge that Armstrong made a significant contribution to help the federation in its anti-doping efforts. UCI documented the payments last October, two contributions totaling $125,000, McQuaid saying then it was “absolute rubbish” to suggest they had been given to cover up a test.

In his January interview with Oprah Winfrey, Armstrong said the donations were “not in exchange for help. They called and said they didn’t have a lot of money; I did. They asked if I would make a donation, so I did.”

McQuaid, last October, contrasting UCI’s finances with those of soccer’s wealthy governing body FIFA, said UCI would still accept such a donation – even now. “But,” he said, “we would accept it differently and announce it differently than before.”

The intent with regard to the lab documents, McQuaid said in the UCI letter, was to present them to a so-called “independent commission” that was under consideration after release of the USADA case against Armstrong. That commission, though, never got going, disbanded earlier this year after discussions with WADA.

Given that development and other issues related to USADA, UCI opted to send the lab results Thursday to WADA.

Armstrong’s “public confession has now lifted any confidentiality issues,” the UCI letter notes.

Armstrong was tested five times during the 2001 Tour of Switzerland – on June 19, 20, 26, 27 and 28.

Three of those five included EPO tests – June 19, 26 and 27.

The accredited lab at Lausanne, Switzerland, conducted the battery of tests.

“As you can see,” the UCI letter says, “every analysis result for Lance Armstrong is reported by the lab as being negative.”

Even so, both the June 19 and June 26 samples contain the same remark. Translated from the French: “strong suspicion of the presence of EPO, the positivity criteria are not all met.”

The June 27 sample simply says, negative.

The June 19 sample was originally tested on July 6; the June 26 sample on July 12. They were sent to and received by the cycling federation after the July 7 start of the 2001 Tour de France, the UCI letter says.

Both samples were then run through more extensive testing.

To simplify the complicated science:

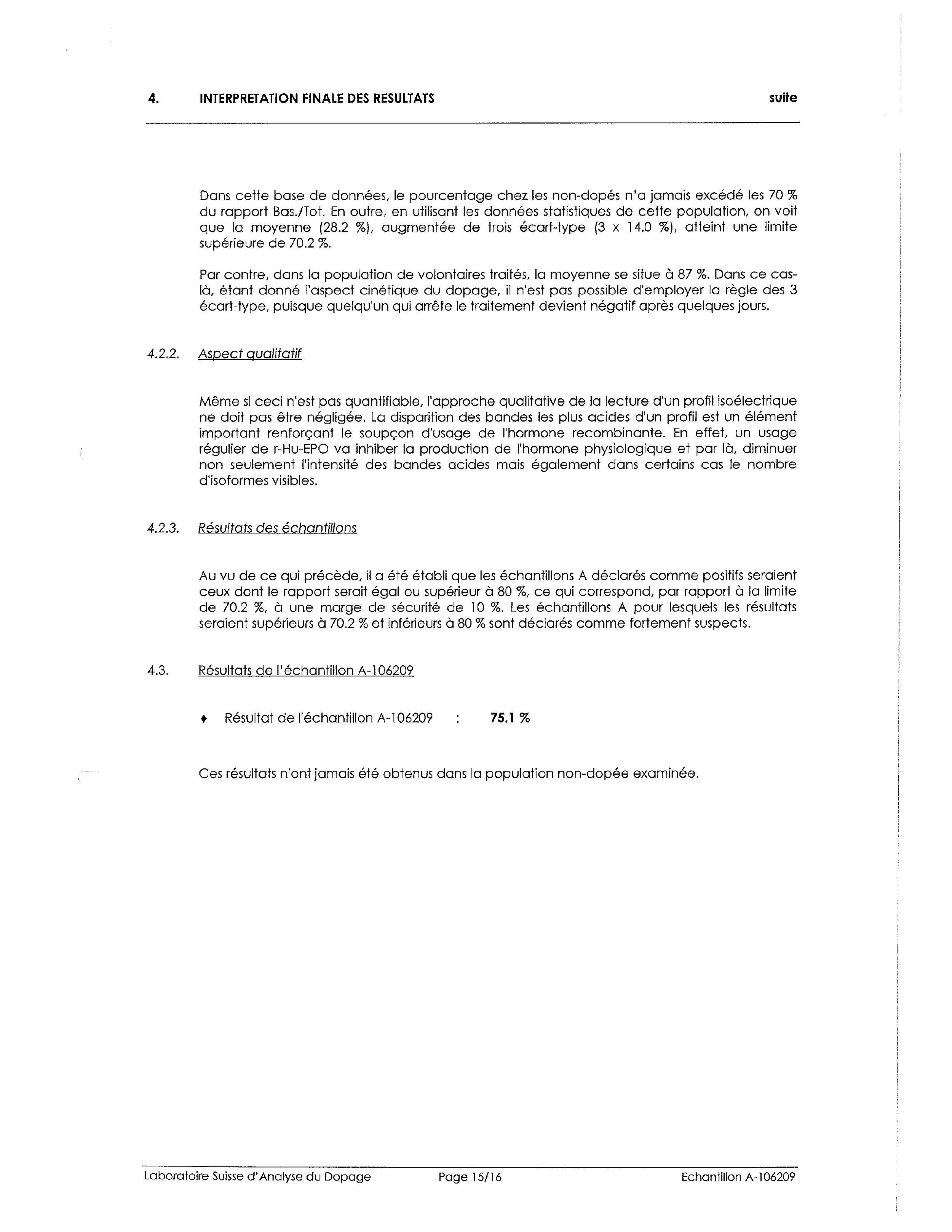

The Lausanne lab considered a sample positive if what are called “basic bands” registered above 80 percent. It considered it “highly suspicious” if it fell above 70.2 and below 80.

Armstrong’s June 19 sample was numbered 106209.

The secondary report was done on Aug. 10, 2001.

The percentage: 75.1.

Armstrong’s June 26 sample was numbered 106106.

The latter report was done on Aug. 7.

The percentage: 70.0.

Even though it fell just outside the category of “highly suspicious,” it was nonetheless categorized that way.

To McQuaid, the conclusion was thus, as he declares on page 3 of the UCI letter: “I reiterate therefore that not one of Armstrong’s samples could in any way have been considered to be positive results.”

The USADA response asserts, in part, “It is now apparent that the UCI has long had in its possession multiple samples from Lance Armstrong which contained synthetic EPO and which raised strong concerns regarding the legitimacy of all of his competitive results since at least 1999. It is shocking and disheartening that the UCI would accept cash payments from Armstrong after the UCI had test results in its possession demonstrating that Armstrong’s samples contained synthetic EPO.”

The USADA letter asks why, among other issues, the UCI did not pursue a case against Armstrong based on those samples and samples from other races in combination with other so-called “non-analytical” evidence, such as witness statements. To not do so, the USADA letter asserts, “appears to have been grossly negligent or worse.”

Armstrong and Bruyneel were told about the suspicious tests during the 2001 Tour de France; Armstrong categorically denied doping, according to the UCI letter. He also questioned the reliability of the EPO test, which had been put into practice just four months before, on April 9, 2001.

During the 2001 Tour de France, Armstrong was tested 10 times, and five times for EPO at the request of the UCI, according to the UCI letter.

The French lab, outside Paris, reported all the results as negative. The highest percentage: 72. This result was not even reported as suspicious, the UCI letter says, noting that the Lausanne and French labs did not use the same criteria.