Back in the day, a young person who was maybe having a little trouble understanding a concept might meet up with an older fella. This older fella might feel so inclined to help impart some wisdom rather directly by means of what in some parts of the United States might be referred to as a switch.

This practice has largely fallen out of favor, given as a switch is pretty much a tree branch and beating people about the head with a stick is no longer considered what we in modern times would call best practice. Actually, we would probably call that a felony.

Even so, when it comes to the race for the 2024 Summer Games between Los Angeles and Paris and, now, perhaps the joined-at-the-hip contest for the 2028 Summer Games, too, let us turn for just a few moments to our new imaginary friend, the common-sense switch.

Good lord.

This is not difficult. Indeed, the way this is trending it is so painfully obvious. It’s truly simply common sense.

Item No. 1:

Tony Estanguet, the Paris 2024 co-president, gets sent to London earlier this week to meet with a gaggle of reporters.

It’s telling that Estanguet is the guy who gets sent to London in the first instance — but let's not digress.

There he delivers through the press an ultimatum: “It’s now or never. We will not come back for 2028. If the IOC can find a solution with Los Angeles, that’s great — but our project is only possible for 2024.”

Reaction: why adopt a black-and-white, either-or position six months before the purported decision date? Ask any sophisticated business person: how often does an ultimatum prove a successful negotiating position?

Item No. 2:

Jules Boykoff, an American professor, writes an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times loaded with trigger words (first paragraph alone: “profit-gobbling cartel” when the International Olympic Committee is not in the business of turning a profit) that asserts, amid all the glibness, that LA and Paris should press the IOC to assume a larger share of cost overruns.

In particular “… it’s time the organization stepped up and contributed to infrastructure costs as well.”

Since 1960, Mr. Boykoff says, “every single Olympics with reliable data has gone over budget, by an average of 156 percent in real terms.”

To be clear:

Zero quarrel here with Mr. Boykoff and his focus on reforming certain elements of the Olympic movement. Trigger words get attention. Mr. Boykoff wants to position himself as one of the Olympic voices in academia to turn to. All good.

The quarrel here is with my former employer, the LA Times, which didn’t challenge the underlying premises of the piece.

A little fact-checking would have made plain what is, again, so obvious — the key distinction between the Los Angeles and Paris plans for 2024, and why, as this space keeps pointing out repeatedly, the IOC would do well to seize the common-sense opportunity right in front of its very face or be prepared to face what the potentially (not being dramatic here) existential consequences.

Because, after 25 years of boondoggles, taxpayers in the west are mightily pissed off.

To explain:

The single most important difference between the LA and Paris bids is that everything that matters in Los Angeles is already built. It exists. Now.

Oops. OK. Wait. Mea culpa. The new NFL stadium in Inglewood doesn't exist yet. But it's being privately financed in a deal driven by the guy who owns the LA Rams. That's a $3-billion, state-of-the-art stadium for which LA24 organizers would not have to pay anything to help construct. So, thanks, right?

Paris would have to build an athletes’ village, media housing and an aquatics complex. Those are big projects, and history shows they inevitably produce cost overruns. They would in Paris. Guaranteed.

The Paris bid files (click here, see pages 28-31) project the village at $1.607 billion, the media housing another $373.8 million. Aquatics would be another $158.05 million. Now you're talking over $2 billion. As an AP story noted, there's also discussion of new public transport infrastructure to make the athletes' village more accessible, via a new train station and construction of a road interchange so that you could get to the village from central Paris in 20 minutes, at least in theory, by car.

Who wants to guess, when the cash register stops wildly spinning and cha-chinging, what obscenely large number would be in neon-bright digits?

And who would end up paying for a big chunk of this?

French taxpayers.

Reality: for credibility purposes, the IOC cannot afford these kind of building sprees anymore, not after 25 years of massive overruns — Barcelona 1992, which jumpstarted the whole Olympics-as-urban-renewal thing, is celebrating its anniversary even now.

Compare and contrast: if you don’t have anything to build, why would you have infrastructure cost overruns? This is the LA story.

Thus to the central thesis of the LAT op-ed piece? Why would the LA24 people want to challenge the IOC on cost overruns when LA24 doesn’t have logical reason to anticipate even one red penny? Hello? LAT editors -- 17 years for me as a staff writer there and have things really gotten that sloppy in the 10 years since I left Spring Street?

Further:

Paris is largely a government project. LA is privately financed. Because LA is a private deal, just like it was in 1984, there is no margin for error, no room for costly boondoggles.

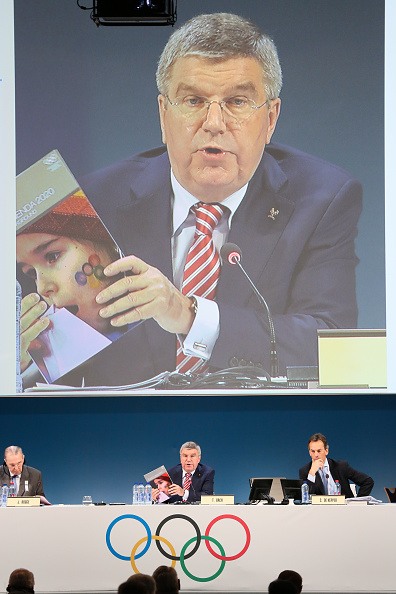

Indeed, LA 2024, early on, considered the construction of a new athletes’ village near downtown Los Angeles. But officials decided not to do it. Why? Because it would have been too expensive! Instead, completely in line with the purported reforms known as Agenda 2020 championed by the IOC president, Thomas Bach, LA 2024 turned to the existing dorms at UCLA. Which are world-class.

Turning to the 156 percent figure:

That comes from an academic survey published last year. Click here if you want to read it in detail. Be mindful that, like any survey, it is only as good as the underlying data — for instance, as it notes, the “vigilant reader” may well be suspicious of some numbers, because “the lowest cost overrun of all Games was found for Beijing 2008,” a reported 2 percent on a reputed $40-billion all-in monster of a bill, because “China is known for its lack of reliability in economic reporting.”

Oh.

At any rate:

You know what else is really fascinating in that survey?

Turn to page 12, Table 3, “Sports-related cost overruns, Olympics 1960-2012, calculated in local currencies, real terms.”

Here, for instance, you see that the Montreal 1976 Games incurred a 720 percent cost overrun.

Barcelona: 266 percent.

You know what’s missing from this chart?

Los Angeles 1984. Totally not there.

Turn, please, to page 25. There the authors have referenced the LA 84 official report. Now turn to page 309 of that official report, section 11.01.10, “Revenue and the operating surplus.” There it says the LA84 organizing committee turned a surplus — attention, LA Times editors, when referring to non-profit enterprises such as the IOC, it’s “surplus,” not “profit” — of at least $215 million, perhaps as much as $250 million.

The final number, as history would prove, was $232.5 million.

Since, through the LA84 Foundation, millions upon millions of dollars have gone into the promotion of youth sport around Southern California. That is real Olympic legacy.

Returning, as we were, to Table 3:

Let’s assume friends in France and Canada (Montreal 76) are more transparent in reporting financial details than friends in China, because these numbers seem genuinely fascinating in considering a Paris bid for 2024:

Grenoble, France, 1968 Winter Games, cost overrun: 181 percent.

Albertville, France, 1992 Winter Games, cost overrun: 137 percent.

Item No. 3:

The California legislative analyst’s office, the state legislature’s nonpartisan fiscal and policy advisor’s arm, issued a report Thursday on the LA24 bid that could not have been more — common sense.

The state, like the city of Los Angeles, has an interest in protecting taxpayers. The reason taxpayers in and around Southern California have repeatedly proven so high on a return of the Games to LA is the consistent belief that a privately run Games will not dent their wallets.

That's just — common sense.

From the report, and be mindful that these legislative offerings tend to prose measured with exacting precision. It is not often one sees “fun” or successful” in the stylings of an official California state report:

“… Los Angeles’ bid makes significant efforts to reduce the financial risks that have plagued prior Olympic cities. Basing its bid on existing or already‑on‑track venues and infrastructure reduces the chance that cost overruns will occur. More broadly, if Los Angeles is selected, Olympic organizers and local leaders can focus largely for the next seven years on preparing the region to host a fun, successful event for athletes and visitors, rather than focusing on keeping big construction projects on time and on budget. We agree with city officials that the current Olympic bid plan is fairly low risk for the city and, by extension, the state as well.”

Jason Sisney, the chief deputy legislative analyst, added in an email, and note again the emphasis from a government official whose No. 1 priority it is to look out for the interest of the taxpayer:

“So far, the efforts of Los Angeles city officials and LA24 to manage financial risks are noteworthy. If Los Angeles wins the Games, this means city officials can spend the next seven years planning a fun, successful event and be less focused on the sometimes thankless task of guiding big Olympic infrastructure projects to completion.”

Let’s once more compare and contrast, because unlike the LA24 people, our Paris 2024 friends would indeed have to guide “big Olympic infrastructure projects to completion,” the biggest that athletes’ village.

If you don’t read French and in particular the fascinating reports detailing notes of interest in immobilier en France, French real estate, perhaps you missed this gem:

Last week saw a building and property trade show in Cannes (that's the sun-splashed ville where they do the film festival). It was called MIPIM.

Who put up a booth?

Paris 2024!

This is itself interesting, since the idea of the stand was to attract private investors but the Paris bid book makes plain that "government" is, for the athletes' village, the "body responsible for funding venue from construction until Games time."

At any rate, maybe the way you go about attracting investors and financing in France is different.

In the United States, you would call, say, Goldman Sachs or some other heavyweight for a project estimated in the billions.

There, it’s a booth at a trade show. What, did our Paris 2024 friends give away pins? Better yet -- some of those 1.5 million Paris 2024 cloth bracelets (2 euros apiece!) that 18 months ago were touted as a crowdsourcing funding vehicle. Maybe a few are now left over?

The story quotes a local dignitary from Seine-Saint-Denis, the Paris suburb where they want to plunk the village:

"This is an opportunity to reduce noise pollution, by creating noise-barriers along the A86 expressway (a major local highway), but also to decontaminate the soils and to place underground the EDF (French utility) electric networks and lines."

This is what an Olympic Games is supposed to be about?

Soil decontamination? Noise barriers? Utility lines?

Or a fun, successful event?

Common sense, people.